Mary Ann Cotton was an English serial killer, perhaps the first in modern English history, who killed her mother, three husbands, a lover and 11 children using arsenic. It has many similarities with the case of Nannie Doss.

Here’s one of the most complete books about Mary Ann: “Mary Ann Cotton: Britain’s First Female Serial Killer”, which was the inspiration for the TV drama ‘Dark Angel’ airing in 2016

Biography of Mary Ann Cotton

Mary Ann was born in England in 1832. Her childhood was signed by poverty and misery, but these, for an average non-wealthy family in the nineteenth century, were the normal conditions of life.

When she was only nine years old her father died while trying to repair the pulley of a well at the mine where he worked. He fell into the well for 150 meters.

Two years later, Mary Ann’s mother remarried, but the little girl and her stepfather never got along. So, at age 16 she decided to leave home to become a maid in a nearby village.

Shortly after her arrival, rumors began to spread about the promiscuous behavior of Mary Ann.

She performed her job perfectly, but when people began to gossip about her relationship with a man of the church, the young girl decided to go back home and learn to be a seamstress.

First husband

At the age of 20 Mary Ann married a miner, William Mowbray, in Newcastle Upon Tyne, and after the marriage they moved to various parts of England due to William’s job that often took him to different places.

In the first four years of marriage the couple had five children, four of which died of gastric fever, a disease that affects the gastric system. Despite the high infant mortality at the time, four dead children were rare, but no one raised suspicions regarding it.

The marriage was not happy, in fact, the couple often fought because Mary Ann did not want to live a poor life; despite that they had other 4 children.

The husband accepted a job on a steamboat in the city of Sunderland, due to which he would have had to spend long periods of time away from home, and Mary Ann and the children followed him, moving to the city.

Three children died of intestinal problems, leaving Mary Ann and William with only two daughters, out of the nine they had during their marriage.

In January 1865 William had to go home to cure a foot injury. Although he was recovering, suddenly he died of an stomach ailment while he was under his wife’s care.

Thanks to the life assurance she had stipulated on her husband’s life, she cashed in 35 pounds, equivalent to at least six months of work.

Second husband

Shortly after William’s death, Mary Ann moved to another city, where she met Joseph Nattrass.

Shortly after William’s death, Mary Ann moved to another city, where she met Joseph Nattrass.

They had an affair but Joseph had a fiancé and unable to break the engagement, he got married, leaving Mary Ann alone.

After Joseph’s wedding one of Mary Ann’s daughters died and the woman sent the only remaining daughter, Isabella, to live with her grandmother and then looked for a job.

She found one in a hospital in the city of Sunderland, where she had returned. Everyone remembers her for her friendliness with patients with whom she often chattered, in particular with one, George Ward.

George was an engineer and fell in love with Mary Ann. Once he was discharged the two got married in August 1865.

Although George was a wealthy man and Mary Ann had moved in with him, she left her daughter Isabella in the care of her mother.

In October 1866, after a long gastric illness, George also died.

His doctor was accused of negligence and Mary Ann was happy. After having collected her husband’s life insurance, she changed city.

Third husband

A month after the death of her second husband, Mary Ann found work as a maid in the home of James Robinson, a ship carpenter who had recently lost his wife and was left alone with four children.

A few days before Christmas, the youngest son of James died of a stomach illness and was buried on December 23, a month after the arrival of the maid in the family home.

Ravaged by grief, James sought solace in Mary Ann’s arms, who became pregnant. They decided to get married, but in March 1867 Mary Ann had to return to her mother’s house: her mother had been taken ill.

When she got to herhouse, the mother was already better, but Mary Ann insisted on staying a few more days to take care of her and to spend some time with her daughter Isabella.

The mother, however, began to suffer from terrible stomach pains and died nine days later. Mary Ann took Isabella and then brought her into James’ home where she died shortly after of a strange stomach ailment, along with two of James’ sons.

The three children were buried two weeks apart from each other at the end of April.

In August, Mary Ann and James got married and in November their daughter, Mary Isabella was born, who died the following March.

In June 1869 they had another son, George, but James began to suspect of his wife, not only for the trail of death brought by the same disease since her arrival in the house, but also for some debts incurred by the woman without his knowledge.

He began to receive several letters from creditors who hadn’t been paid. He decided to ask his children if they knew anything, in order not to make Mary Ann suspicious, who in the meantime was pressing him to stipulate a life insurance policy, and

the children told him they had been forced to sell objects from the house to a pawn shop and to hand over the money to their stepmother.

After discovering the truth, he kicked Mary Ann out of the house, keeping custody of little George. Mary Ann ended uplivingin the street.

James was the only man to survive.

Fourth husband

After living in the street for some time her friend Margaret Cotton introduced her to her brother, Frederick Cotton, who had recently become a widowed and had lost two of his four children.

Margaret had become like a second mother to Frederick’s two sons, Frederick Jr. and Charles. Unfortunately, she too died of a strange, sudden stomach ailment

and Frederick, distraught, found solace in the arms of Mary Ann just like her previous husband did.Exactly like on that occasion, Mary Ann became pregnant.

They married in 1870 although Mary Ann was still married to James Robinson. After the marriage she began to take care of the house and bought insurance on her husband and her two son’s life.

In 1871 she gave birth to the little Robert and the same year she learned that her old flame, Joseph Nattrass, lived nearby and was not married.

With a ruse she persuaded the family to move closer to Joseph and soon lost interest in her husband, who died a few months later of a sudden “gastric fever”.

The two lovers

Left alone, she began to rent a room to her lover, Joseph, and sought work as a nurse to make some extra cash.

She started working for a man who was recovering from smallpox, John Quick-Manning, and she soon became pregnant of his child.

Now Joseph and Frederick’ sons became an obstacle to this new relationship and in March 1872 Frederick Jr died, shortly followed by Robert.

Mary Ann did not want to bury Robert because Joseph in the meantime had also suddenly fallen seriously ill. Mary Ann, thinking that he would die soon too, preferred to wait to organize only one funeral.

The woman was right, and Joseph died a few days later Robert, after signing a will to leave all this belongings t to Mary Ann.

The last murder of Mary Ann Cotton

Now only Charles Cotton was left for her to get rid of. First she asked a man of the parish, Thomas Riley, if he could send him to a hospital for the poor.

The man replied that it would be possible only if she had gone there too.

Mary Ann refused and confessed to the man that the child was getting in the way of her marriage to another man, but that soon he would no longer be a problem because, she said,

“he will go away like everyother Cotton”.

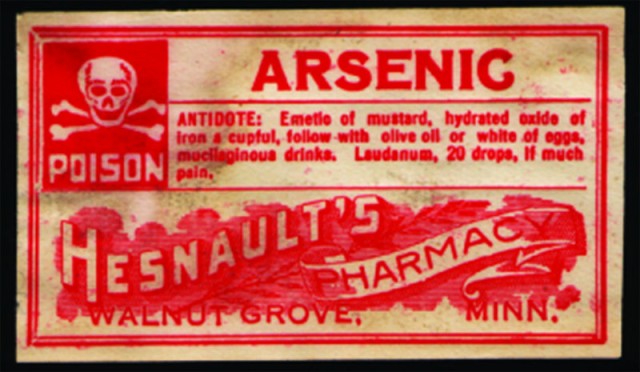

She sent the young Charles to buy arsenic, then used as a disinfectant, but the pharmacist refused to sell the substance to someone under 21.

She then sent a neighbour to buy the product and in July Charles too died suddenly of intestinal problems.

Thomas, after becoming aware of the child’s death, became suspicious and went to the police where he told them about his previous encounter with the woman.

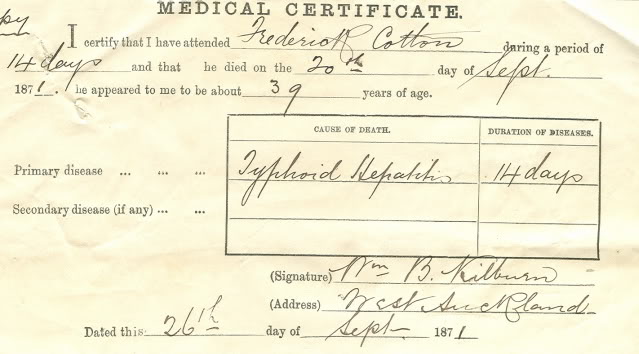

Meanwhile, Mary Ann had gone to the bank to collect the money from the insurance policy on Charles’ life, but she were denied the money because she didn’t have the death certificate with her.

She went to the doctor who informed her that he was being investigated by the police and that he could not issue a death certificate until the end of the investigation.

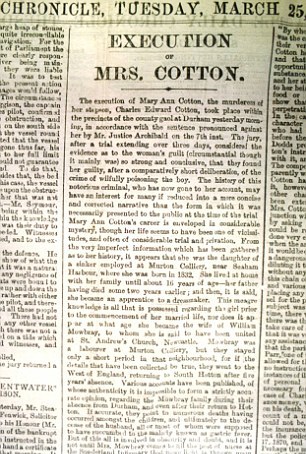

Arrest and conviction

Investigations began and rumors started spreading about Mary Ann. The newspapers began to talk of poisoning and John, her husband to be, broke contact with her.

Investigations began and rumors started spreading about Mary Ann. The newspapers began to talk of poisoning and John, her husband to be, broke contact with her.

The woman, left alone, began preparations to change city. The forensic doctor, however, discovered remains of arsenic in Charles’ stomach and Mary Ann was arrested.

The body of Joseph was exhumed and in his stomach they found remains of arsenic too.

Her trial began in March 1873 and was attended by many witnesses. Many testified that they had seen her buy arsenic and many others told of her previous victims.

The defense argued that Charles had not ingested the poison, but had breathed it in because it was part of the substance used for painting the walls of the house. The judge withdrew to deliberate and after just 90 minutes declared Mary Ann Cotton guilty of the murder of the little Charles and sentenced her to death by hanging.

While waiting for the date of her death sentence, Mary Ann asked acquaintances and friends to sign petitions to free her, but it did not work and on the 24 March 1873 she was taken to the scaffold.

The Executioner made a mistake and Mary Ann, instead of dying soon because of a broken neck, was left agonizing for at least three minutes, slowly being suffocated by the rope.

How could Mary Ann Cotton get away with poisoning so many people without arousing suspicion?

First of all, the living conditions at the time were not the best, especially in poor families, and one death from intestinal problems did not arouse suspicions.

Secondly arsenic was readily available at the time, because used as a disinfectant, and its ingestion caused vomiting and diarrhea.

Deaths from poisoning, therefore, were often mistaken for gastric fever (or typhoid), a disease that attacked the intestinal system.