According to a Mayan legend, there are 13 crystal skulls and, if brought together in the same place, they would cause something extraordinary to happen.

The legend of the crystal skulls

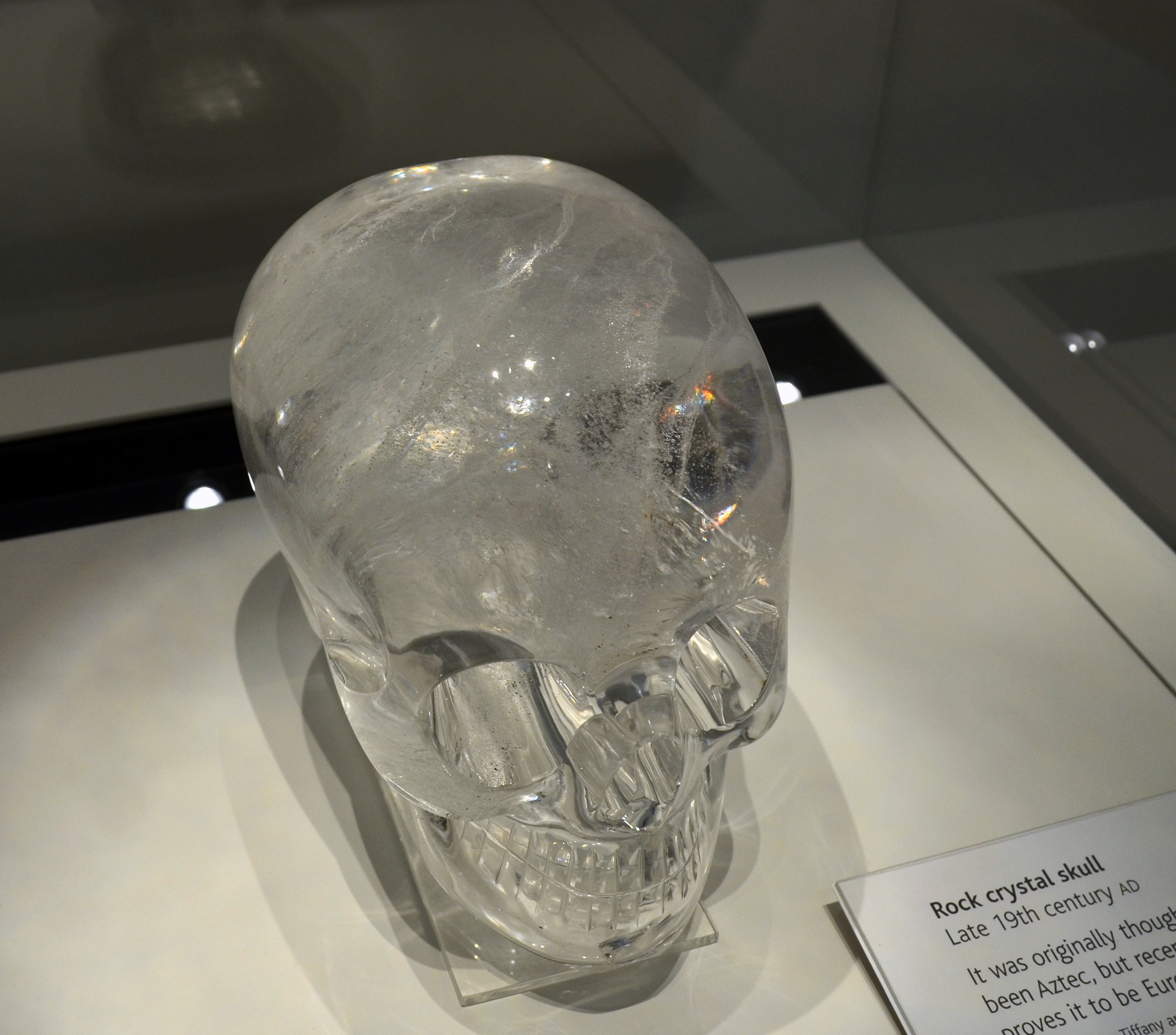

Crystal skulls are fascinating sculptures carved from a single block of transparent, milky or coloured quartz. Their anatomical perfection and impossible smoothness have fuelled intriguing theories for decades: relics of ancient lost civilisations, instruments of shamanic power or even artefacts of extraterrestrial origin.

These enigmatic objects are often associated with the Mayan and Aztec cultures, peoples who did indeed frequently depict skulls in their sacred art. However, unlike traditional Mesoamerican stone sculptures, crystal skulls are distinguished by their extraordinarily precise workmanship, which has puzzled scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Some researchers, such as those at the British Museum, argue that they are skilful 19th-century fakes. Others, especially in the New Age culture, continue to believe in their connection to ancient prophecies and paranormal powers. The truth, as is often the case, may lie somewhere in between: extraordinary works of art that have fuelled the myth thanks to their beauty and our thirst for mystery.

The lost origins

The origin of crystal skulls is closely linked to the figure of Eugène Boban, a French antique dealer who worked in Mexico City between 1860 and 1880. Boban became the main supplier of these mysterious artefacts, presenting them as authentic pre-Columbian finds. His collection, which included at least three crystal skulls, was later purchased by ethnographer Alphonse Pinart and donated to the Musée de l’Homme in Paris.

One of the most famous skulls, now kept at the British Museum, made its first appearance in 1881 in Boban’s Paris shop. The antique dealer tried unsuccessfully to sell it to the Mexican National Museum as an Aztec artefact. The skull then changed hands several times: it passed through the hands of George H. Sisson, was exhibited in 1887 during a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and was finally purchased at auction by Tiffany & Co., which resold it to the British Museum in 1897.

Another famous specimen, the so-called “Mitchell-Hedges Skull”, has an equally controversial history. According to the official version, it was discovered in 1924 by Anna Mitchell-Hedges, the adopted daughter of adventurer F.A. Mitchell-Hedges, during excavations in Lubaantun, Belize. However, subsequent research has shown that Mitchell-Hedges actually purchased the skull in 1943 from Sydney Burney, a London art dealer, at a Sotheby’s auction. The first official documentation of this skull dates back to 1936, when it appeared in an article in the British anthropological magazine Man as the property of Burney.

As early as the late 19th century, scholars such as William Henry Holmes, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution, had expressed doubts about the authenticity of these artefacts. In 1886, Holmes published an article entitled “The Trade in Spurious Mexican Antiquities” in the journal Science, warning against the thriving market in fake pre-Columbian artefacts. His insights would only be confirmed a century later by modern scientific analysis.

Theories about the origin of crystal skulls

Theories about the origin of crystal skulls have evolved significantly over time. Initially, these artefacts were presented as authentic pre-Columbian artefacts, attributed mainly to the Aztec and Mayan civilisations. Their alleged discoverers and dealers, such as Eugène Boban, claimed that they were ritual or ceremonial objects dating back to ancient times.

Some supporters of the skulls’ authenticity, including Anna Mitchell-Hedges, put forward intriguing hypotheses about their use. Mitchell-Hedges claimed that the skull in her possession had been used by Mayan high priests for esoteric rituals and that it had the power to cause death through the power of the mind. However, these claims are not supported by historical sources or the spiritual traditions of Mesoamerican cultures documented by scholars.

In academic circles, theories about the skulls’ provenance took a different direction. Researchers noted that the skulls did not display stylistic characteristics consistent with known Mesoamerican art, nor were there any similar artefacts found in verifiable archaeological contexts. Furthermore, analysis of the material revealed that the quartz used came from deposits in Brazil and Madagascar, geographical areas with which pre-Columbian civilisations had no known contact.

The most widely accepted hypothesis among scholars is that the skulls were made in Europe in the 19th century, probably in the workshops of Idar-Oberstein, a German town renowned for its crystal work. This theory is supported both by the manufacturing techniques identified, which show the use of modern tools, and by historical documentation linking many specimens to the European antique market of the time, in particular to the commercial network of Eugène Boban.

Despite the scientific evidence, some pseudo-historical and New Age movements continue to claim mysterious origins for crystal skulls, linking them to alleged lost civilisations or esoteric knowledge. However, these theories are not supported by official archaeological and historical research, which considers them to be the result of modern speculation rather than real ancient traditions.

Science Unveils the Mystery

Scientific investigations conducted since the 1960s have provided definitive answers about the origin of crystal skulls. Researchers at the British Museum were among the first to subject specimens in their collections to in-depth examination in 1967, 1996 and 2004. Using electron microscopes and X-ray crystallography techniques, they identified unmistakable signs of processing with modern rotary tools, completely foreign to pre-Columbian craft techniques.

Particularly revealing was the analysis of chlorite inclusions in the quartz, which showed that the material came exclusively from Brazilian or Malagasy deposits, impossible to find for Mesoamerican civilisations. The final blow to theories about ancient origins came from a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science in 2008, which highlighted the use of industrial abrasives such as carborundum (silicon carbide), invented only in the 1890s.

Even the famous Mitchell-Hedges skull, examined in Hewlett-Packard laboratories in the 1970s, revealed characteristics incompatible with a pre-Columbian origin. Despite the claims of owner Anna Mitchell-Hedges about alleged paranormal powers, scientific tests confirmed that it was a modern artefact, probably made in the 1930s as a copy of the skull in the British Museum.

Further confirmation came from analyses conducted at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris between 2007 and 2008, where dating using the quartz hydration technique unequivocally established that the so-called “Paris Skull” had been carved between the 18th and 19th centuries. These results were perfectly consistent with historical documentation linking many of the skulls to the activities of the merchant Eugène Boban in the second half of the 19th century.

The scientific community is now unanimous in its conclusion: all the crystal skulls examined using modern methods have been found to be 19th-century European creations, made to exploit the growing demand for exotic antiquities in the collectors’ market of the time.

Why does the myth persist?

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence attesting to their 19th-century origin, the skulls continue to exert a persistent fascination in the collective imagination. This phenomenon has its roots in a complex overlap of cultural and psychological factors. Anna Mitchell-Hedges, the last owner of the most famous specimen, personally fuelled the mystique surrounding the object, claiming to have received premonitory visions and attributing healing powers to it. Her claims found fertile ground in the growing New Age movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

The esoteric narrative was further enriched by the publication of works such as Serpent of Light by Drunvalo Melchizedek, who placed the skulls in a context of supposed Mayan wisdom and improbable spiritual ceremonies. At the same time, popular culture helped spread these beliefs through films, documentaries and television series that emphasised the mysterious side of the artefacts. For example, the documentary The Mystery of the Crystal Skulls (2008), produced for the Sci Fi channel, mixed pseudo-history and fantasy archaeology, going so far as to hypothesise connections with extraterrestrial civilisations. Although lacking any scientific basis, the programme reached a wide audience, consolidating the idea of skulls as objects “impossible” to make with ancient technologies in the popular imagination.

Crystal skulls between myth and reality

Exposed by science as clever 19th-century forgeries, crystal skulls remain fascinating symbols. Their history reveals more about modern man than about the ancient past: our thirst for mystery survives even scientific truths. More works of art than relics, they remind us that sometimes the real magic lies in the power of the imagination.