The rites linked to death have been one of the most intriguing aspects of the vast anthropological universe for thousands of years. These rituals not only have the primary purpose of honouring and remembering the dead, but also of exorcising death itself. From the great civilizations to the most remote tribes, from the most remote antiquity to the present day: there are many rituals elaborated by the men of yesterday and today.

Rituals, however, that often lead to the macabre, the invasion, the fanaticism, the gore and – depending on the laws in force – the most driven illegality.

What we are going to illustrate is, without a doubt, one of the bloodiest and most brutal funeral rituals. We’re going to India, to discover the macabre practice of the Sati.

From divinity to earthly practice

In Sanskrit is सती. Sati.

It is from this ancient Hindu divinity that the name of the macabre funeral practice derives. To fully understand the origins of this ritual it is necessary, at least in extreme synthesis, to enter into the complex world of the Hindu pantheon and the most rooted philosophical and religious traditions of India and the East.

Sati is the personification of Prakṛti: an abstraction of thought difficult to understand which, for simplification, can be associated with our concept of “Nature” or, even better, “primordial driving force”. Brahmā, the creator of the Universe, wants “Nature” to take human form.

Sati is the daughter of Dakṣa – one of the sons of Brahmā – and Prasūti. Sati will become the wife of Siva, one of the most important male divinities of Hinduism. The marriage, however, is opposed – in vain – by Dakṣa.

The following episode will give rise to the origin of the practice of the ritual. Dakṣa dare not invite Sati and Siva to a Yajña, a particular ritual of sacrifice. Sati, however, decides to go to the ritual anyway and face his father. The episode generates a quarrel between Dakṣa and Sati, who – deeply wounded by the behavior of her father – sacrifices herself, starting to burn from the bowels of her body. Another version of the story states that Sati throws herself into the flames of the sacrificial fires used during the Yajña.

Siva, at that moment in meditation on Mount Kailash, perceives what happened. He then generates Virabhadra, a vindictive demon who will slaughter all those who have opposed Sati and Siva himself. Even Dakṣa will not be spared and will be beheaded.

Sati, the sacrifice of the widows

The myth and the tales related to Sati do not end with his sacrifice but, in our case, it is sufficient to dwell on the particular origin of this myth, that is, the immolation of Sati. A mythological episode from which, however, the practice – absolutely real – of the Sati is born.

It seems that the first documentary traces of this macabre funeral practice date back to around 510 BC; a clue in this sense comes from a stele erected in the ancient city of Eran, located in the current Madhya Pradesh, India.

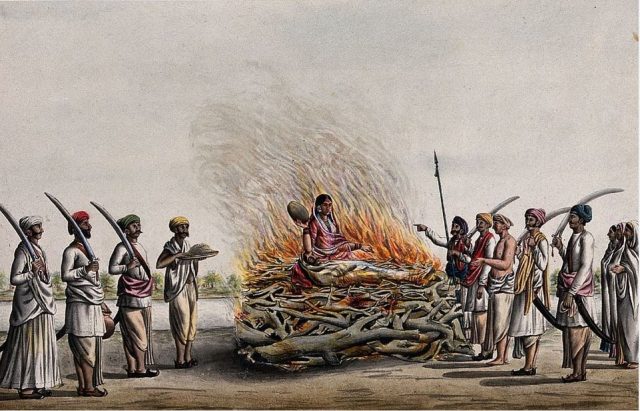

What is the funeral rite of the Sati? The ritual foresees that, after her husband’s death, the widow throws herself alive in the flames of the funeral pyre set up for her husband. A real immolation, a ritual suicide.

In ancient times, there were various “unofficial” types of ritual. In northern India, the woman is tied to a pole and burned alive by means of a brazier made of bamboo and wood filled with fatty substances, in order to make combustion more efficient.

In Bengal, on the banks of the Ganges, another form of ritual is consumed: the woman, sprinkled with combustible substances, is tied to the body of her deceased husband and set on fire in a brazier of straw and palms. In other places in India, however, the brazier is buried.

The ritual suicide of widows is, obviously, a profound, supreme act of conjugal devotion to their spouse. In fact it is a suicide but, in the shoes of the Indian people, the term “suicide” seems improper. For women, indeed, the funeral practice of the Sati is a reason for pride and social redemption: not all women can aspire to the Sati and those who perform their immolation are particularly deserving.

All the Indian social castes embrace this practice but, since the widow’s property is donated as an inheritance to her deceased husband’s family, the Sati extends above all to the wealthiest and most socially influential castes, including priests and soldiers.

Not all multiform India accepts this practice. Sikhs, Muslims of the Moghul dynasty, many Hindus prohibit or reject this practice, which many – already in the past – called barbaric and useless. The westernisation of India – which over the centuries has become a colony of the most important European countries – leads to a gradual ban on the practice of the Sati. It was Lord William Bentinck, Governor General of Bengal from 1828 to 1835 who abolished by law – in 1829 – the practice of the Sati, an operation also supported by the Raja Ram Mohan Roy, a leading figure in Indian reformism.

The abolition, however, does not have the desired effect. In some areas of India (especially those with less literacy), the practice resists, even in the form of coercion against widows, forced to sacrifice themselves.

The chronicles written by the British East India Company offer a measure of the “Sati phenomenon”: from 1813 to 1828, an average of about 600 cases of Sati immolations are calculated per year. These are also figures that are likely to be downwards: the practice of the Sati was, in fact, much more widespread.

The phenomenon, from 1829, will gradually fade away; in contemporary times, there are more than 50-60 documented cases from 1947-1950. Documented in fact: the cases of Sati not ascertained, unknown or interrupted could, indeed, be many more.

As in the years following its abolition, the Sati is still performed today in particularly poor and remote areas. Moreover, certain cases open discussions and debates, even at political level, on the legitimacy or otherwise of a funeral practice rooted in the deepest traditions and social fabric of India. Documented the controversial cases of Roop Kanwa (18 years old who died in 1987), Charan Shah (55 years old, 1999), Vidyawati (35 years old, 2006), Janakrani (40 years old, 2006).

Sati: from deity to macabre sacrifice. Religious fanaticism, blind exaltation, visceral, impenetrable devotion: ingredients of that macabre suggestion called Sati.

This practice is also described in Jules Verne’s book “Around the world in 80 days”.