When we talk about “witch-hunting”, the memory and the collective imagination run to an ancient past made of tortures, burning at the stake, death sentences, superstition and popular beliefs. A vast and very complex period of time, generally limited to the years from 1330 to 1700. A historical period often distorted by literature, by vast cinematography, rich in recurrent stereotypes and still the subject of in-depth studies. It is therefore difficult to imagine a trial for “witchcraft” in the middle of the Second World War. All this, however, is a reality and the case that we are going to see has a very important historical value. Helen Duncan is, in fact, one of the last people to be condemned and imprisoned for “witchcraft” under the Witchcraft Act 1735.

Who is Helen Duncan

Victoria Helen McCrae MacFarlane was born on 25 November 1897 in Callander, a Scottish town in Perthshire, from Isabella and Archibald MacFarlane. Since her school years, Helen has shown presumed supernatural and clairvoyant abilities, arousing fear and mistrust among teachers and pupils. In a period of time, she continually thinks about the number “1066”. During a history lesson on the Battle of Hastings – dated 14 October 1066 – the professor was struck by a heart attack. The mother, worried about the disturbing signs and alarmed by the particular psychology manifested by her daughter, has Helen examined by a doctor. The doctor does not find any physical anomaly. On the contrary, it is the doctor who is the victim of a prophecy. Helen tells him not to leave the house, but the doctor disregards the girl’s words: he will die in a car accident, during a snowstorm. The Minister of the local Presbyterian Church accuses Helen of “consorting with the Devil”.

When she was 16 she left her family and went to Dundee. The First World War raged in Europe: first she worked in an ammunition factory, then as a nurse at the Dundee Royal Infirmary. Here, Helen, thanks to Jean Duncan – her best friend who she met in the workplace – meets her future husband, Henry Duncan, Jean’s brother. The two of them were married in 1916.

The Duncan couple, of course, do not live comfortably: she, first of all, tries to earn as much as she can by washing and repairing sheets and shirts, he – a war invalid, suffering from rheumatic fever and with a compromised heart valve – gets by working as a carpenter. They have six children: Bella, Nan, Lillian, Henry, Peter and Gena. Two more die at an early age.

Henry is also struck by a heart attack (not fatal: he will die in 1967), an episode that Helen had predicted. Henry encourages Helen to develop her powers of clairvoyance, chiaroudience, psychometrics and precognition (skills also known by the names of foreknowledge, foreknowledge, foreknowledge and foreknowledge).

It is in this phase that Helen and Henry Duncan begin, probably, to conceive the scenic expedient of the ectoplasm and to exploit in a systematic way – for profit and sensationalism – the presumed, self-styled mediumistic capacities of Helen. It all began on a night when Helen, in a deep state of trance, heard the voice of a certain Dr. Williams, who would ask Henry to exploit the powers of his wife Helen in order to evoke and materialize the spirits of the deceased. The spiritual sessions are repeated and follow each other more and more frequently and in the presence no longer only of friends and neighbors. The (paying) audience widens and the Duncan couple increase their fame: Helen becomes a sought-after and respected medium.

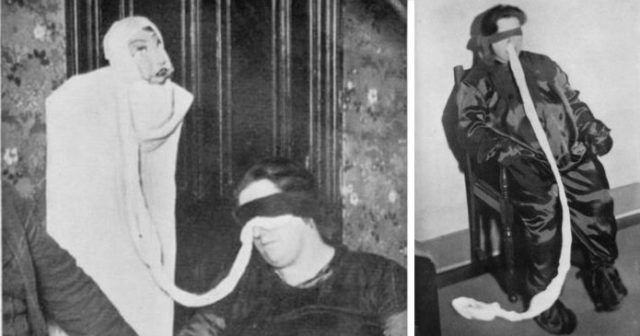

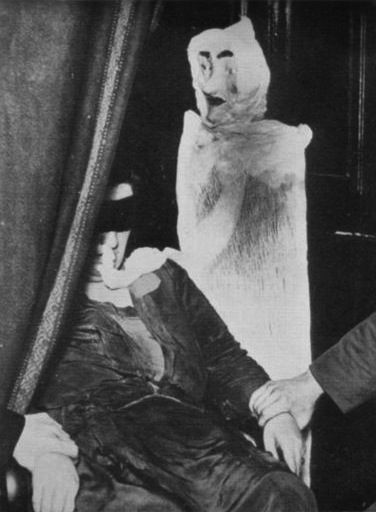

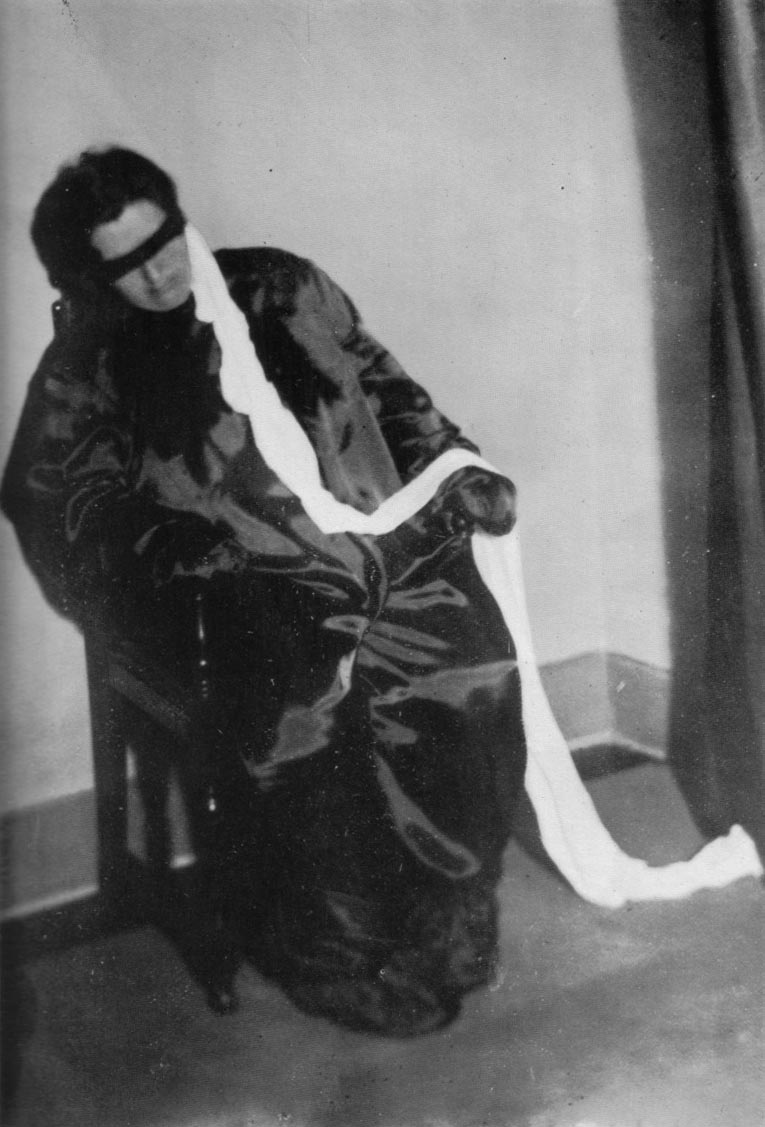

It is in these séances that Helen manifests the notorious ectoplasm, substance of a bright white described as “magic fog” or “living cobweb”. This ectoplasm comes out of her mouth and nostrils. This is how the figures of Albert Stewart (“Uncle Albert”) and “Peggy” were born, spiritual guides that materialize during the sessions. “Uncle Albert” is an elderly person, Scottish emigrated to Australia, who drowned and died in 1913. A sort of ceremonialist who appears from the white and mysterious ectoplasm. “Peggy”, Helen’s other spiritual guide – is a girl who reveals herself during the session singing songs. In the 1920s, Helen became a national case and her mediumistic abilities attracted favours and, of course, doubts and unveiled mistrust. Earnings also begin and Henry, in fact, becomes the manager, the “prosecutor” of Helen. The picture of the grotesque situation, however, begins to emerge in a clear and evident way.

In 1928, thanks to Harvey Metcalfe’s photographs, Helen’s already precarious and dubious medium and supernatural gifts began to shake visibly and emerge for what they really were: a colossal scam. In 1931, the London Spiritualist Alliance (founded in 1884, now known as the College of Psychic Studies) examined the methods used by the Duncan couple, examinations aimed at analysing and possibly unmasking the Duncan scam.

Harry Price – a renowned parapsychologist and founder and director of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research – is the one who definitively unmasks the unique fraudulent methodologies devised by the Duncan couple.

The ectoplasm, in reality, is a mixture of cheese-making fabric, egg white, paper and other materials that are easy to shape (to hide and make appear at the right time), ingestable and then regurgitated. Even spirits are only puppets made with papier-mâché. Harry Price tells and retraces the story of Helen and Henry Duncan in the book “Leaves from a Psychist’s Case Book” (1933) in the chapter entitled “The Cheese-Cloth Worshippers”. The numerous photos document and highlight in a clear and incontrovertible way the clumsy scam staged by Helen and Henry Duncan.

Duncan’s scams followed one another throughout the 1930s, including fake séances, detailed scientific analyses refused, moments of escalation, fines and convictions. On January 6, 1934 (other sources indicate 1933), in Edinburgh, Helen Duncan performed yet another scam: the usual session, the evocation and materialization of the spiritual guides and the deceased, the appearance of “Peggy”, which, however, is nothing more than a puppet in a petticoat. She will be fined 10 pounds and convicted for the crime of fraudulent mediumship on May 11, 1934. The trick will be unmasked, in this circumstance, by Miss Maule. Helen was given the opportunity to denounce Miss Maule but Duncan declined the offer. Throughout the 1930s, however, the Duncan’s activity continued unabated, meeting with both the support and opposition of the public and experts in the field. This led to the Second World War.

The case of HMS Barham

In 1941, when the Second World War (1939-1945) had been going on for two years now, Helen Duncan – thanks to her spiritual guide Albert – revealed facts that had yet to happen or confidential information that had not yet been made public. This happened during two sessions, dated 24 May 1941 (Edinburgh; reveals the entry into the war of the Soviet Union and the sinking of the HMS Hood) and November 1941 (Portsmouth). However, the meeting of November 1941 at the important and nerve-wracking port city of Hampshire made history. On this occasion, in fact, Helen Duncan came into contact with the spirit of a deceased sailor, who told her of the sinking of HMS Barham. The spirit of Barham’s sailor materializes in the room, as per the script: he wears a military cap with “Barham” written on it. The hat, however, is fake. The British military do not wear hats with the inscription of the ship.

The HMS (acronym for His or Her Majesty’s Ship; during World War II it was “His”, since King George VI reigned) Barham was a prestigious battleship of the Queen Elizabeth Class: launched on October 31, 1914, put into service on October 19 of the following year. The control of the Mediterranean Sea constitutes a fundamental element in the economy of the military strategies, English and Italo-German. Well, securing air and sea superiority in this specific area is tantamount to establishing a strategic and tactical dominance that extends from North Africa to Italy, from the Balkans to the entrance to the Middle East.

The Barham left the port of Alexandria in Egypt on November 24, 1941. The following day, HMS Barham, while on a mission off the Egyptian coast against some Italian convoys flanked by the HMS Queen Elizabeth, the HMS Valiant and eight destroyers, was mortally hit by three torpedoes launched by the German submarine U-Boot 331 (it was later sunk by the British on November 17, 1942), commanded by the Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen. 841 (other sources indicate 861 and 862) sailors die in the huge explosion of the santabarbara (instant immortalized in photos passed down in history) and in the consequent sinking of the British battleship. The survivors’ figures also oscillate: some sources say 395, other say 450. In any case, the Barham – one of the most significant battleships in the Royal Navy – has been lost.

The question is, how does Helen Duncan know about the sinking of the HMS Barham? How do you know about a fact that happened a few days earlier and hasn’t yet been reported? Did this happen exactly like this? Let’s analyse the facts.

The British Admiralty is trying to hide the news of the sinking of the prestigious battleship. However, the Royal Navy’s top management brief the family members of the Barham crew about the incident, telling them not to release the news before the official statement is formalised.

In fact, the information – which was intended to be kept secret until the official announcement of January 1942 – gets out of hand, causing the chain of secrecy to break; “The Times” reports the sinking a few days after the event.

Helen Duncan, even in this circumstance, does not demonstrate mediumistic and clairvoyant abilities. Once again, she relies on the credulity of the people and on puppets pretended to be spirits of deceased people. Securing such an important sinking that involves hundreds, thousands of people is, in fact, pure utopia. News escaped from the military channels and from the relatives of the Royal Navy sailors themselves allow the news to spread like wildfire sooner than expected. Especially in a port city like Portsmouth, teeming with soldiers, families of soldiers committed to the front, constantly at the center of the chronicles of war. The relatives of the crew members aboard the Barham confide in other people who, in turn, talk to other people; other soldiers report what happened and, within a few days, the news is already in the hands of public opinion. The chatter becomes insistent, creeping, contagious and Duncan, smelling the greedy scoop, uses these rumors. Playing on this ambiguity and on the misunderstanding of the still unofficial news of the sinking of HMS Barham, Helen Duncan is able to stage yet another pseudo-median artifice. All this mechanism is well explained and illustrated in the book “Loose Cannons: 101 Myths, Mishaps and Misadventurers of Military History” (2009), written by Graeme Donald.

The Royal Navy military, however, follow and monitor Helen Duncan’s activities. In 1944, here is the turning point.

Helen Duncan’s conviction: the Witchcraft Act 1735

In January 1944, following another session, Helen Duncan was arrested. Two sailors of the Royal Navy: the Lt. Worth and Fowler assist this session, dated 19 January 1944 and organized in Portsmouth, precisely in Copnor Road. The two were assisted by two policemen, Cross and Taylor. Worth – according to Duncan’s mediumistic revelations – has an aunt and sister deceased. In fact, the Lt. R.Worth has no deceased aunt and his sister is also alive and in good health. At this point, the policemen intervene and interrupt the session and arrest the Scottish medium.

Initially, Duncan was indicted according to the extremes set out in Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act 1824, an act that sanctioned begging. In this Section various and numerous forms of wandering, obtaining fraudulent money as well as the practice of palmistry and the like are contemplated (i.e. sanctioned), as the original text states:

[…]Every person committing any of the offences herein-before mentioned, after having been convicted as an idle and disorderly person; every person pretending or professing to tell fortunes, or using any subtle craft, means, or device, by palmistry or otherwise, to deceive and impose on any of his Majesty’s subjects.

[…]every person wandering abroad, and endeavouring by the exposure of wounds or deformities to obtain or gather alms; every person going about as a gatherer or collector of alms, or endeavouring to procure charitable contributions of any nature or kind, under any false or fraudulent pretence.

However, the judicial authorities consider Helen Duncan’s position much more serious and worthy of exemplary condemnation.

It is at this moment that the Witchcraft Act 1735 enters the scene. This ancient law punishes those who practice (or rather, those who boast of possessing supernatural powers) “magic”, “witchcraft” and various forms of fraudulent spiritual, psychic and mediumistic activities. The maximum penalty is 1 year imprisonment. The Witchcraft Act 1735 should not be considered as the ideal continuation of the harsh persecution of the so-called “witches”, typical of the 1400, 1500, 1600 and 1700 (just think of the case of Anna Maria Schwegelin or Schwägelin, protagonist of the last documented case of “witch-hunting” in Germany: we are in 1775).

In Scotland, for example, there are over 200 convictions for witchcraft from 1563 to 1727 (other sources indicate, probably wrongly, the year 1722). It is in this year, in fact, that “Janet Horne” (real or presumed name) is burned alive for witchcraft in Dornoch, Sutherland: she is accused of using her daughter as a pony to “ride towards the Devil”. The daughter has a malformation in her hand, enough to accuse the woman of witchcraft. Janet Horne and her daughter are both convicted and imprisoned, but the daughter manages to escape. But Janet Horne’s fate is marked: naked and sprinkled with tar, she is locked up in a barrel and set on fire as she is carried in procession.

The Witchcraft Act 1735, therefore, is presented as a more modern law, daughter of the values of the Enlightenment, in contrast to the previous and indiscriminate persecutions based on superstition and beliefs result of a distorted and violent religiosity. Thanks to the Witchcraft Act 1735, therefore, the figure of the witch commonly understood, to be condemned as an expression of the Devil, is lost, but attempts are made to stem the phenomenon of so-called gurus, mediums, witches. A law, if you like, still relevant (except for the reference to the word “witch”) and that marks the way to the most modern legislation against fraud and deception. The Witchcraft Act 1735 finds in James Erskine, Lord Grange, the most assiduous (and perhaps only), real opponent: he, in fact, believes in the existence of witchcraft.

Together with Helen Duncan, the “companions” of the scene are indicted: Ernest and Elizabeth Homer and Frances Brown.

The trial is short and is celebrated from March 23 1944 to the 3rd of April of the same year at the Old Bailey in London, the building that houses the Central Criminal Court. Helen Duncan was sentenced to 9 months in prison, later reduced to 6 months. She served her sentence in the London prison of Holloway, active from 1852 to 2016; she was released on September 22, 1944, under the promise – unfulfilled – not to perform any more sessions. Helen Duncan, who had been ill for some time (diabetic and severely obese), died on December 6, 1956, at the age of 59, not before having held a last session, still interrupted by the police.

Helen Duncan, however, was not the last person to be condemned for magic and witchcraft. Jane Rebecca Yorke is another English medium arrested and convicted under the extremes of the Witchcraft Act 1735. Her sentence – following her arrest in July 1944 – will be of mild entity: a pecuniary sanction and a good conduct to be held in the following three years. A benevolent jury against a 72-year-old woman.

In 1951, also at the behest of Winston Churchill (Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 May 1940 to 26 July 1945 and from 26 October 1951 to 6 April 1955), the Witchcraft Act 1735 was replaced by the more modern and updated Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951, also aimed at suffocating any fraudulent activity related to the so-called mediums.

It is Churchill himself who defines the “Helen Duncan case”, the clamour found among the British people, the wide resonance given by the press to this case as well as the controversial recourse to the Witchcraft Act 1735 as “tomfoolery”. The charismatic English politician and ex-military writes unkind words to Herbert Morrison, of the Ministry of the Interior. He reproached the British judiciary for having lost time in these matters, with witnesses transferred – at the expense of the State – from Portsmouth to London, stealing time, money and resources from the concrete activities of the courts. But Churchill’s contribution to Helen Duncan’s case has also been masterfully distorted and exaggerated, to the point of bordering on the urban legend. Churchill does not want to help or demonize Helen Duncan, thus placing herself in an intermediate position. And, to tell the truth, he doesn’t show so much interest in the story itself. There is war and the Prime Minister has other thoughts on his mind…

The Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951, in turn, will be repealed on 26 May 2008 with the introduction of the Consumer Protection Regulation 2008, aimed at more general consumer protection.

The controversial chapter on Helen Duncan’s historical legacy now opens. Idolized by many, contested by many others. Even today, Duncan’s relatives, spiritualists, mediums and sympathizers of various backgrounds and nature of this type of activity and practice defend Helen Duncan’s work. According to this group, Duncan really had supernatural abilities, she was really able to get in touch with deceased spirits and reveal facts and information otherwise unknown and yet to occur. And she was really able to generate the famous ectoplasm. This group, in justification of their positions, maintains that police and judiciary have never come into possession of overwhelming evidence of Duncan’s guilt, testifying, that is, fraudulent practices. On the contrary, they reply, saying that it was all a sort of “conspiracy” designed by MI5 (Military Intelligence, Section 5) to silence an uncomfortable person who could have revealed, first of all, the plans of “Overlord”, the landing in Normandy, the D-Day (June 6, 1944). Not only: it is said that, in the 1944 session in which Duncan was arrested, the military tried in vain to grasp the ectoplasm. Duncan’s relatives and “followers” promoted a petition (now closed), a posthumous Forgiveness. This initiative, however, has been repeatedly rejected by the Scottish Parliament.

On the other hand, there is a large group of scientists, experts in the field, researchers, historians and journalists who label all the activity set up by the Duncan spouses as fraudulent, product of lies and skilful staging. The evidence, they say, is overwhelming, starting with Harry Price’s exams, evidence challenged in the course of Helen Duncan’s brief trial. Already at the time of the facts, experts and scholars have analyzed the activity of the Duncan through rigorous scientific analysis. Verifications which today, for example, are constantly carried out by the CICAP (Italian Committee for the Control of Statements on Pseudosciences).

We are, in the end, talking about a woman who in several circumstances has manifested a psychology – using a terminology that is not orthodox but simplifying – “disturbed”: attacks of anger, self-punitive behaviour. Henry himself – her husband – is described as a manipulative subject. The fraudulent nature of Duncan’s spiritual sessions and powers is probably sanctioned by the photographs taken during the sèances; photographs that fully highlight the grotesque “do-it-yourself” characteristics of the techniques employed by the Duncan couple: clothes designed to conceal the crude artifices on stage, gloves that can be glimpsed coming out of the “ectoplasm”, the textile and “homemade” nature of the ectoplasm itself, mannequins passed off as spirits and so on.

The anachronistic charm of the “Helen Duncan case”

The story of Helen Duncan, regardless of the contrasting positions, arouses an undeniable fascination. A fascination that we could define anachronistic, in which the personal history of a medium is mixed with History, the one with a capital “S”: the Second World War. A diplomatic intrigue all “made in United Kingdom” that winds between “witchcraft” and military history, spiritualism and naval battles, mediumistic practices that go beyond human perception and science.

A news that still holds its own today, thanks to that tantalizing anachronistic fascination generated by the “exhumation” of a legislative act – with over 200 years on its back – that seemed forgotten, shelved forever, obsolete, no longer applicable in the modern and progressive twentieth century, in the middle of World War II.

With Helen Duncan, and later with Jane Rebecca Yorke, the last remaining flame of that long and obscure chapter that has bloodied Europe and not only: the “witch hunt” is extinguished. The Witchcraft Act 1735, although it was a breaking point with the real persecution of witches, keeps intact the reference to that historical period. If Helen Duncan had been prosecuted and persecuted under other laws, this story would not have taken on the contours that we all know.

“Witch”: when a word makes a difference and can write history.