An enigma that has lasted since 1703, Italy, France and Paris are the backdrop to one of the most intricate and complex events in European history. A detective story involving kings and their wives, philosophers, thinkers, writers, politicians, historical and symbolic places of a France still ruled by Louis XIV of Bourbon, the so-called “Sun King”, king of France from 1643 to 1715.

From Voltaire the first testimony

François-Marie Arouet (Paris, 21 November 1694-Paris, 30 May 1778), the first name of that versatile man of culture who went down in history under the pseudonym of Voltaire. It was the famous Parisian thinker who gave life to the legend of the “Iron Mask”.

In 1717, following some satirical, pungent and politically incorrect verses against Duke Philip of Orléans – who, in fact, moved the strings of a young Louis XV, King of France – and the Duchess of Berry (Marie Louise Elizabeth of Orléans), Voltaire was imprisoned at the Bastille.

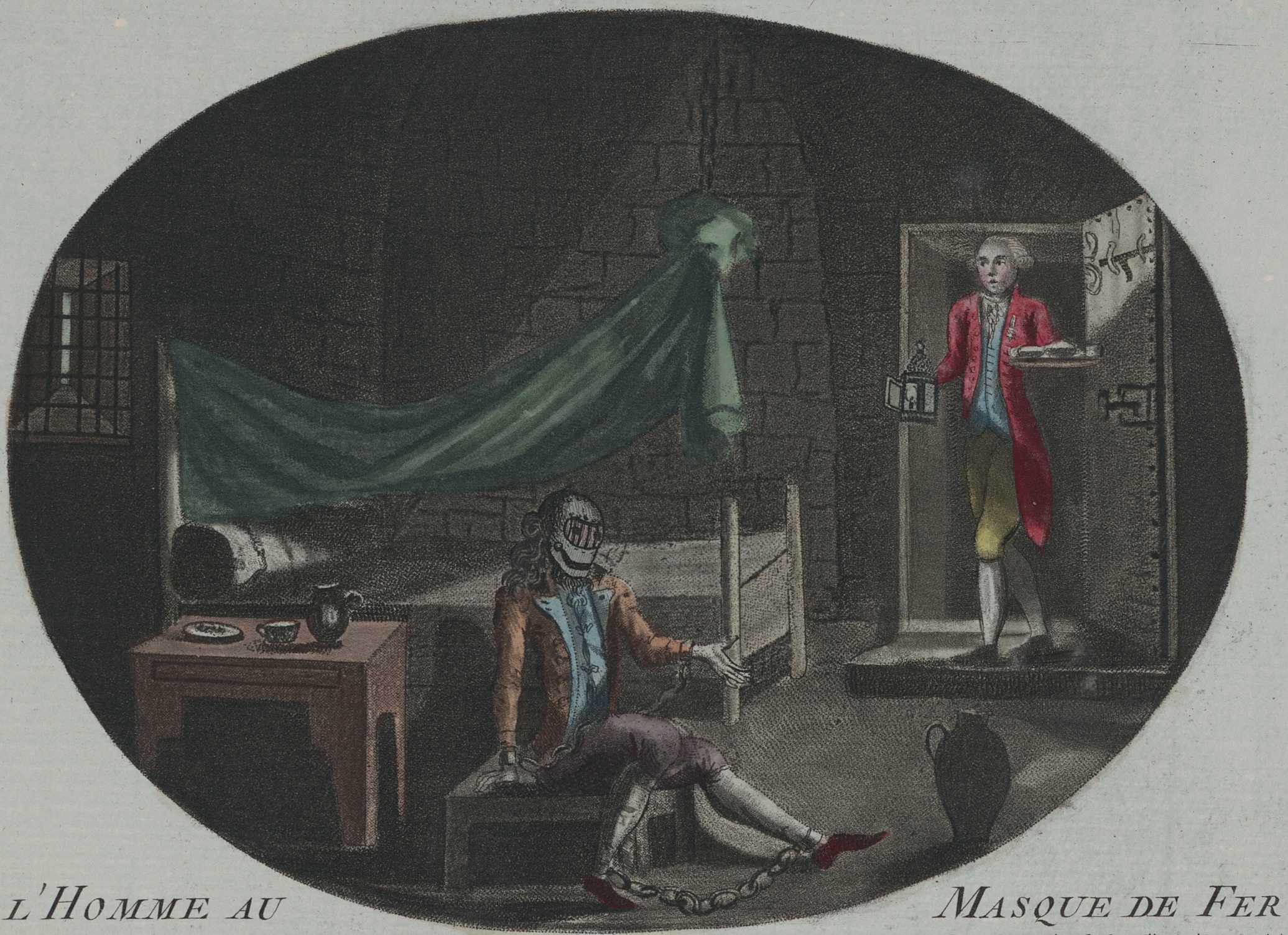

During his imprisonment in the prisons of the iconic Parisian fortress, Voltaire learns of some stories about a strange, enigmatic prisoner who, years earlier, had been detained at the Bastille itself. This prisoner, with an unknown identity, wore in his face a unique mask of black velvet, characterized by metal straps to support it. The face, therefore, was deliberately kept hidden.

He was indeed a very special prisoner: an important figure, well treated by his own jailers. Plenty of good food, books and a lute to cheer up the long, grey days of the mysterious prisoner.

Voltaire wants to know more about this dark story.

Documents already mention the mysterious prisoner in 1687: no one can pronounce his name and his face is hidden by an “iron mask”, such as to prevent the recognition of the man.

Voltaire’s research reveals partial shreds of truth. The prisoner, who has gone down in history as “Homme au masque de fer” – “the man with the iron mask”, in fact – seems to have died on November 19, 1703, more precisely around 10 PM. Ignored, however, are the identity of the prisoner, his age (the parish register of the church of Saint-Paul-des-Champs indicates 45 years) and the causes that led to his detention at the Bastille.

Buried in the no longer existing cemetery of Saint-Paul-des-Champs, it was the governor of the Bastille himself, Benigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, who attended the funeral. And it was Saint-Mars himself who supervised and took personal care of the prisoner even in the phases of detention prior to the Bastille. A real “shadow man” in charge of assisting “ad personam” the mysterious – and important – prisoner. Why all this secrecy?

“Iron Mask”: which is the real identity?

The mystery that revolves around the identity of the man with the iron mask invests several levels, which move between historical reality, legend and even literary inventions.

It seems that the prisoner arrived at the Bastille in 1698. Before being taken to Paris, the prisoner was first imprisoned for a long time (it is said that he had been imprisoned for 12 years) in Pinerolo (Turin; 1669), then – between October 1681 and April 1687 – at the Fort of Exilles (Turin), then he was transferred to the fortress of the Island of Santa Margherita, off Cannes. This, then, is the tormented and tortuous process that leads “Iron Mask” to the Bastille.

As mentioned earlier, the treatment of the enigmatic prisoner is particularly benevolent. In this sense, the governor of the fortress of the Bastille (and already head of the citadel of Pinerolo), Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, received precise directives from François Michel Le Tellier, Marquis of Louvois, important secretary of state for the war under the reign of Louis XIV. Why such respectful treatment of this mysterious prisoner? Is it, then, a leading figure in European politics and society of the time impossible, however, to condemn to death? Is he, in any way, related to the French royal family? Is this, perhaps, the reason why the prisoner is forced to wear – except during meals and during the hours of rest – a mask that constantly conceals his face, and therefore his real identity? Between misrepresentation and legend, the enigma becomes thicker and more and more compelling.

The “case” of the Iron Mask: a real intrigue?

One fact is certain: the name found engraved on the tomb in the cemetery of Saint-Paul-des-Champs is clearly fictitious: Marchiali according to some, Marchioly or Marchialy. Three variations, all three certainly fake. So, what is the real, authentic identity of “Iron Mask”?

Voltaire, therefore, is the one who opens the doors, in a decisive and complete manner, to the legend of the man who went down in history with the nickname of “Iron Mask”. In chapter 25 of the work entitled “Le siècle de Louis XIV” – written and followed by “Supplément” (1751, 1752, 1753), “Suite de l’Essai sur l’Histoire générale” (1763) and “Questions sur l’Encyclopédie” (1770 and 1771) – Voltaire makes bold and clamorous hypotheses.

He hypothesized that the “Iron Mask” was a twin brother or half-brother of the King of France, Louis XIV. A brother who, for political reasons never ascertained, King Louis XIII (father of Louis XIV) and Anna Maria Maurizia of Habsburg (known by the name of Anne of Austria, wife of Louis XIII and mother of Louis XIV) have duly concealed from the French people and the nobility of the time. The hypothesis, evidently, that it would rewrite the history of the Bourbons and of that European nobility so high and powerful as “gelatinous” and “lurid” with regard to blood ties and not only.

But that’s not all. What if “Iron Mask” was the natural father of Louis XIV? Well, this fascinating conjecture takes shape from some historical data that is worth analyzing.

Louis XIII, father of Louis XIV, married Anne of Austria on 24 November 1615; the latter was the daughter of King Philip III of Spain and Margaret of Austria. Louis XIV was born, however, only in 1638, more precisely on 5 September in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Louis XIV had a brother: Philip of France, Duke of Orléans, born on September 21, 1640.

A particularly long period of time and, therefore, suspect at the time. Why did 23 years pass between the wedding and the birth of the first-born? What determined this long wait? Did the four abortions – at the time, infant mortality reached very high peaks -contribute?

Well, it is not known. There are those who believe that the cause of this long wait is the unhappy climate and not at all relaxed within the royal couple, but there are those who believe there is something much more “itchy”.

Perhaps it has something to do with the presumed impotence of Louis XIII? Is this, therefore, the hypothesis at the root of the mysterious identity of “Iron Mask”?

Is “Iron Mask”, then, the natural father of Louis XIV?

At the death of Louis XIII (which will take place on May 14, 1643), in fact, the Bourbon dynasty risks collapse, the end. Still without children, therefore, the throne of France would have been due to the brother of Louis XIII, that Gaston d’Orléans badly seen by the family itself and by the political and ecclesiastical leaders of the time, beginning with the influential Armand-Jean du Plessis – the well-known Cardinal Richelieu – and Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino. Not only badly seen but also without sons.

In order to guarantee heirs to the king and queen, as well as to ensure the royal Bourbon lineage, the “deus ex machina” of the French royal palaces would have organized, handed down a plan as ingenious as it was simple: instead of King Louis XIII, the royal thalamus would have seen as the male protagonist another man, who, under lavish compensation, would thus have guaranteed children, that is, heirs. A man, however, still of Bourbon blood.

Is Louis XIV’s natural father an Iron Mask?

Questions, doubts, conspiracies, dark machinations, games of power and blood, hidden mysteries and probably never revealed. If this hypothesis were true, Louis XIII would not be Louis XIV’s father. Given the strong resemblance between the true father and Louis XIV, the royal family opted for a drastic solution: to eliminate any trace of Louis XIV’s true father. How? Passing the man off as a prisoner of life and concealing his face by means of a black velvet mask supported by metal straps.

A conspiracy vision certainly fascinating but not at all proven by incontrovertible facts. Who, then, is the biological father of the second son of Louis XIII and Anne of Austria, Philip of France, Duke of Orléans? Louis XIII, who would not be powerless, or another man? Perhaps still the one who, years later, will be imprisoned and go down in history as “Iron Mask”?

Other identities: many hypotheses, few certainties

Official historiography, although it has no certain elements to shed light on the true identity of “Iron Mask”, cautiously rejects the thesis that “Iron Mask” is the biological father of Louis XIV. Historians, in fact, are inclined to other alternative readings of the events related to “Iron Mask”.

The road leading to Nicolas Fouquet is weak. Minister of Finance under Louis XIV, he was arrested in 1661: embezzlement and fraud. In short, an unreliable person (but wrongly accused, according to other historical sources) who badly administers the royal finances. Fouquet was thus imprisoned at the fortress of Pinerolo.

Fouquet died on March 23, 1680, in Pinerolo, due to a stroke. A weak thesis: why hide the identity of an already known person?

Another “suspect” is Count Ercole Antonio Mattioli (Valencia, 1 December 1640-Cannes, 1694), Italian politician and diplomat, collaborator of Duke Ferdinand Charles of Gonzaga-Nevers, Charles III. Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga instructed Mattioli to cede Casale Monferrato (Alessandria) to France. 500,000 Scudi: this is the price of the deal, very secret and confidential. When he arrives in Turin, however, the “wheeler-dealer” reveals the reason for his journey. The result is a diplomatic case: Spain and Austria, in fact, are also interested in buying the Piedmontese territory. It seems that Mattioli acts as a sort of “spy”, a double-crosser selling information to Spain about the deal. Arrested in 1679, he was taken to the Pinerolo prison under the false name of Lestang, and finally taken in the fortress of the island of Santa Margherita. We are already in 1694. Death will come shortly after, in April of the same year. For the record, Casale Monferrato passed into French hands in 1682.

Why, then, conceal the identity of Ercole Antonio Mattioli with a fictitious name and an iron mask? Apparently, the Italian politician was arrested in an illegitimate way, that is, in a way that did not comply with the laws and territorial powers of an Italy that at the time was fragmented and disputed. How to cover up a burning diplomatic case? By concealing the real identity of the prisoner, in his name and likeness. An iron mask hiding his face.

Testimonies and coincidences play in favour of this hypothesis. First of all, some testimonies dating back to the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV (son of Louis of Bourbon, Duke of Burgundy, and Maria Adelaide of Savoy), who would refer to a man linked “to the Duke of Mantua” (Gonzaga, in fact) and to an “important minister of an Italian prince”. Finally, there is a certain similarity between the fictitious names engraved on the tomb of “Iron Mask” and the surname Mattioli: Marchiali, Marchioly and Marchialy are misprints of the real surname, Mattioli?

Other data, however, deny this version of the facts. Mattioli’s arrest is known to the politics and society of the time. Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga-Nevers himself was informed, and Mattioli’s name appeared in the correspondence between François Michel Le Tellier, Marquis of Louvois, and Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars. In short, Mattioli does not seem to be “Iron Mask”.

Other characters then come into play. In fact, none of them convinces, even though it was some scholars and historians who brought these individuals into play. They range from Charles de Batz de Castelmore, known as d’Artagnan, to the dwarf Nabo, a black slave from whom Maria Theresa of Habsburg (wife of Louis XIV and daughter of Philip IV of Habsburg, king of Spain) would have a son. And more: from Giovanni Gonzaga to Eustache Dauger, a valet imprisoned in the fortress of Pinerolo in 1669 and, according to some, the protagonist of a unique exchange of identity with the already mentioned Nicolas Fouquet. The road that leads to Vivien L’Abbé, seigneur de Bulonde, a high-ranking soldier during the conquest of Cuneo, is also sluggish. Intimidated at the sight of Austrian troops, he left the battlefield. He was imprisoned. Is Vivien de Bulonde “Iron Mask”? Probably not.

The legacy of “Iron Mask”

“The Viscount of Bragelonne” is the work that has contributed significantly and decisively to the spread of the legend linked to “Iron Mask”. Written by Alexandre Dumas, father (Villers-Cotterêts, 24 July 1802 – Puys, Dieppe, 5 December 1870), it completes the so-called “cycle of musketeers”, composed of “The Three Musketeers” (1844), “Twenty years later” (1845) and, in fact, “The Viscount of Bragelonne” (1848).

“The Viscount of Bragelonne” appeared for the first time in 1847 in the newspaper “Le Siècle”, published in instalments. The historical novel takes up the events of “Iron Mask” and embraces the theses launched by Voltaire. The centre of the plot lies precisely in the identity that Dumas attributes to the “Iron Mask”. In fact, in the text, the enigmatic life imprisonment is called Philip, imprisoned at the Bastille in disguise and with the name of Marchiali. Philip is none other than the twin brother of the King of France, Louis XIV. The king himself ignores the existence of this brother. Between twists and turns, conspiracies, machinations, dark plots of power, misunderstandings, the presence of musketeers and mistaken identities (Louis XIV is arrested and Philip takes the throne of France for a short time), the order is restored at a high price: Philip is again taken prisoner, taken to the fortress of the island of Santa Margherita and forced to wear a mask made of iron.

Novels, essays, a rich filmography. “L’homme au masque de fer” (Iron Mask) has been able, since the diffusion of its history, to capture the attention of artists, scholars and simple lovers of history and mystery.

With this character we are in the presence of an authentic historical and literary puzzle. History, legend, pure literary invention? As in the very different case of Jack the Ripper, the hypotheses about the identity of “Iron Mask” follow one another, more or less imaginative, without interruption. Many names, no historical certainty.

And here, inevitably, history gives way to myth, to legend. A very evocative character, that of “Iron Mask”: he immediately catapults us into France, into those European courts thirsting for power, into scenarios of imposing fortresses and dark and filthy galleys.

A prisoner without face and identity, which legend, literature and films have transformed almost into a real “monster”, a creature sometimes superhuman, suspended in time and space. His face, hidden by a disturbing mask – which the myth and the stories that have followed over time have turned from velvet to heavy iron – has now become an immortal icon.

And this is perhaps the true legacy of “Iron Mask”. A character who transcends his presumed, true identity and his historicity.

Discordant sources, equally uncertain testimonies, dates and names that are anything but in focus.

Only one truth, probably, remains and will remain certain: we will never know the true identity of “Iron Mask”. The legend continues…