The Mary Celeste is perhaps the most famous ghost ship, and its mystery has intrigued everyone since the day it was found. Completely devoid of crew and with no signs of a struggle, what secret does it hide?

A timeless mystery

In the vast ocean of unsolved mysteries, few have captured the collective imagination like that of the Mary Celeste, the ghost ship par excellence. Its name has become synonymous with unexplained disappearances, puzzles that defy logic and stories that lie halfway between reality and legend.

Launched in 1861 in Nova Scotia under the name Amazon, the ship seemed doomed from the start: its first captain died of pneumonia shortly after launch, and a series of accidents (fires, collisions, shipwrecks) tarnished its reputation. Renamed Mary Celeste in 1869, the ship seemed to find a new lease of life until that fateful November of 1872, when it set sail from New York bound for Genoa with a cargo of denatured alcohol and a crew of ten, including Captain Benjamin Briggs, his wife Sarah and their two-year-old daughter Sophia.

What happened in the weeks that followed remains one of the greatest mysteries in maritime history. On 4 December 1872, the Mary Celeste was spotted adrift in the Atlantic, between the Azores and Gibraltar, by the British ship Dei Gratia. There was no sign of the crew on board: the ship was deserted but strangely intact. The sails were unfurled, the cargo almost completely intact (apart from nine empty barrels), and personal belongings, clothes and even food on plates remained in the cabin, as if everyone had suddenly disappeared. The lifeboat, sextant and chronometer were missing, while a metre of water flooded the hold and a pump had been dismantled. There were no signs of violence, mutiny or sudden emergency. Only silence.

Many questions, no answers

Since that day, theories have multiplied relentlessly. Perhaps alcohol vapours caused fears of an explosion, prompting the crew to flee in the lifeboat, which was then lost at sea? Or perhaps a waterspout, a tidal wave or a navigational error prompted the captain to abandon ship in a hurry? There has been talk of pirates, mutiny, ergot poisoning and even extraterrestrial intervention. The official inquiry in Gibraltar found no answers, further fuelling the myth.

The Mary Celeste continued to sail, now as a cursed relic, until 1885, when its last owner deliberately sank it in a clumsy attempt at insurance fraud. But its mystery has survived, fuelled by novels, films and documentaries. Today, more than 150 years after those events, the question remains: what really happened on board the Mary Celeste?

This article traces its history, from its origins to the most plausible theories, to the cultural legacy of a legend that still fascinates and disturbs us today. Because, after all, the sea holds secrets that may never be revealed.

The origins of the ship, from Amazon to Mary Celeste

The story of the Mary Celeste has its roots in the foggy coasts of Nova Scotia, where in 1861 it was launched under the name Amazon by the small community of Spencer Island. This 31-metre, 282-tonne brigantine was the first major shipbuilding project completed by the local shipyard, a source of pride for the region, but one that soon proved to be tainted by a disturbing series of misfortunes.

From its maiden voyage, the ship seemed to carry a curse. The first captain, Robert McLellan, died of pneumonia just nine days after taking command, beginning a grim tradition that would see three captains lose their lives on board in the following years. Under Captain John Nutting Parker, the ship collided with a fishing boat, followed by a mysterious fire that broke out during repairs.

1867 marked a turning point in the ship’s history. After running aground during a violent storm in Glace Bay, the Amazon was sold for a pittance – just $1,750 – to Richard Haines of New York, who invested $8,825 to restore it to seaworthy condition. This change of ownership marked the beginning of a new era: in 1868, the ship was transferred to the American shipping register and completely refurbished, changing its name to Mary Celeste the following year.

The new life of the Mary Celeste

The new owners, including future captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs, who owned 8 of the 24 shares into which the property was divided, had big plans for the ship. The intention was to use it for lucrative trade across the Atlantic, with a particular focus on the Adriatic ports. The 1872 refurbishment, which cost the considerable sum of $10,000, added a second deck and increased the length of the hull to 103 feet (31.2 metres), transforming the Mary Celeste into a modern and spacious brigantine, seemingly ready to leave its turbulent past behind.

Yet, as subsequent events would prove, the ship seemed unable to escape its fate. This phase of apparent rebirth would last less than a year, until that fateful November 1872 when the Mary Celeste set sail on the voyage that would consign it forever to the pages of history as the most famous ghost ship of all time.

The last journey

November 5, 1872 marked the beginning of the most enigmatic voyage in modern maritime history. The Mary Celeste, now under the command of respected Captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs, a 37-year-old experienced sailor with an impeccable reputation, set sail from Staten Island harbour bound for Genoa. On board, in addition to the captain, were seven crew members personally selected by Briggs, his wife Sarah E. Briggs and their two-year-old daughter Sophia Matilda. The couple’s eldest son, Arthur, had remained ashore to attend school, a decision that may have saved his life.

The cargo consisted of 1,701 barrels of denatured alcohol (worth approximately $35,000 today) destined for Italian industry, transported on behalf of the Meissner Ackermann & Coin company. It was a dangerous but lucrative cargo: denatured alcohol, although not drinkable, could release flammable vapours under certain conditions.

The calm before the storm.

The first few days of sailing were relatively calm, but on 25 November, the logbook recorded the ship’s approach to the Azores, specifically the island of Santa Maria. This would be the last official entry. According to reconstructions, the ship was actually about 120 nautical miles from its estimated position at that time, an error probably caused by a faulty chronometer that had compromised the navigation calculations.

In the following days, the Mary Celeste faced increasingly adverse weather conditions. Modern analysis of climate data from the time (using the ICOADS database) reveals that the ship was in the midst of winds exceeding 35 knots and rough seas. It was in this context that the unthinkable happened: ten people vanished into thin air, leaving the ship perfectly seaworthy, with its sails still set and its precious cargo virtually intact.

Particularly significant was the subsequent discovery of the dismantled pump and the metre and a half of water in the hold. These elements, combined with the presence of the “sounding rod” (the instrument for measuring the water level) left on deck, suggest that the crew had carried out frantic checks before disappearing. The absence of the lifeboat, sextant and marine chronometer, together with the disappearance of some ship’s documents, added further layers of mystery to an already inexplicable story.

Captain Briggs, an experienced navigator with an impeccable career behind him, had personally chosen each member of the crew, all respectable professionals with no history of mutiny or violent behaviour. Among them were First Officer Albert Richardson, the Danish Second Officer and the two German brothers Volkert and Boye Lorenzen. None of them would ever see land again.

The discovery: a ship without a soul

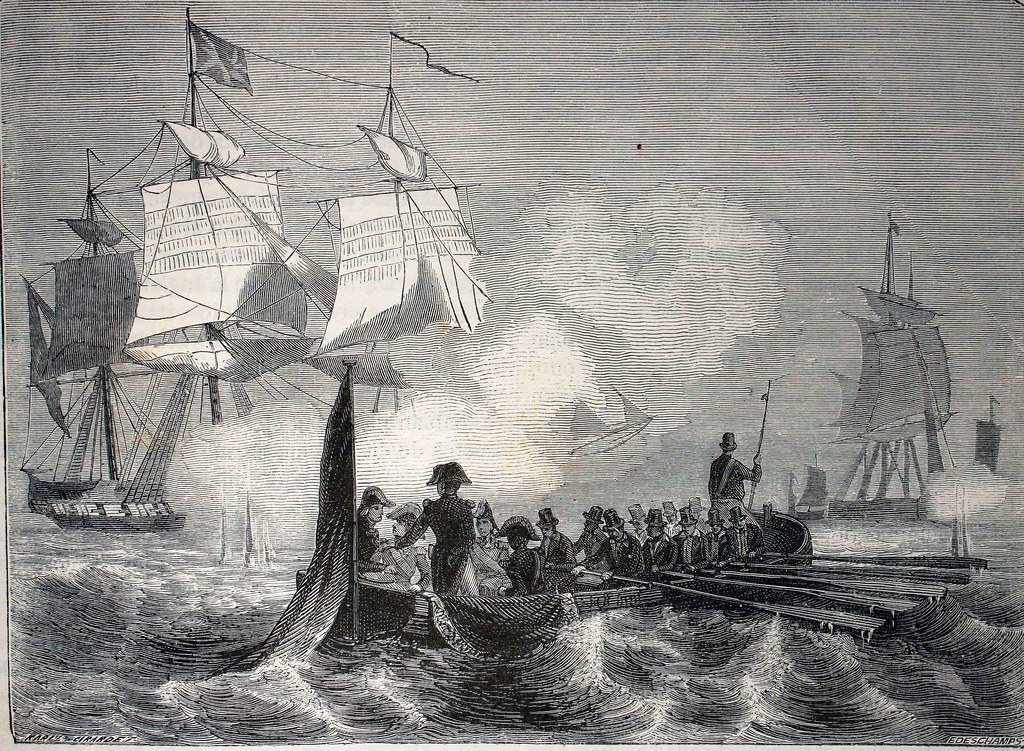

On 4 December 1872, at coordinates 38°20′N 17°15′W, approximately 400 miles east of the Azores, one of the most disturbing sightings in naval history took place. The British brigantine Dei Gratia, commanded by Captain David Morehouse, a casual acquaintance of Captain Briggs, came across a ship sailing erratically, with its sails partially lowered and listing unusually. To their surprise, they recognised the Mary Celeste, which had left the same port of New York eight days earlier and should have arrived in Genoa some time ago.

Morehouse, suspicious of the lack of response to his signals, sent first officer Oliver Deveau with two sailors aboard the mysterious ship. What they discovered would generate a mystery that would last for centuries. The Mary Celeste was completely deserted, but showed contradictory signs that suggested a sudden but not catastrophic abandonment:

The condition of the ship:

- Approximately 1 metre of water in the hold (not dangerous for stability)

- One pump dismantled and the other in operation

- The galley with pots still on the stove

- Plates set with uneaten food

- Beds unmade as if occupied until recently

- The logbook was present but the pages for the last 7 days were missing

- The captain’s cabin in order, with the Briggs family’s personal belongings intact

- 9 of the 1,701 barrels of alcohol empty (all red oak, more porous)

- The lifeboat missing, with its supports damaged

- The compass destroyed and the sextant/chronometer missing

- A 10-metre rope hanging into the sea from the hull

Disturbing details:

- All food and water supplies for 6 months intact

- No signs of violence or struggle

- The alcohol cargo almost completely intact (except for the 9 barrels)

- The sails unfurled but poorly adjusted, some torn

- The main hold door closed, no signs of explosion

Deveau and his men, after a careful inspection, decided to take the Mary Celeste to Gibraltar, about 800 miles away. This was no easy feat with only three men on board, but it was made possible by the ship’s good overall condition. The journey took 11 days, during which they noticed that the ship was perfectly capable of sailing despite everything.

The Gibraltar investigation

When the Mary Celeste docked in Gibraltar on 13 December 1872, the official investigation quickly turned into a court case distorted by the preconceptions of prosecutor Frederick Solly Flood, who was convinced from the outset that he was dealing with a crime. Using primitive investigative methods, Flood ordered wood samples to be taken in search of traces of blood (analyses that proved inconclusive), examined every corner of the ship for signs of violence, and even went so far as to hypothesise a conspiracy between Captain Briggs and the captain of the Dei Gratia, despite the absurdity of the theory given that Briggs was co-owner of the ship and had left all his belongings on board.

Flood fixated on the crew of the Dei Gratia, accusing them of orchestrating the whole thing to collect the rescue reward, and put forward increasingly bizarre theories, from collective drunkenness (ignoring that denatured alcohol was poisonous) to an unlikely mass murder without any evidence. His three-month investigation proved to be a maze of unfounded suspicions, while crucial details—such as the deviation from the original course, which only emerged decades later in his personal notes—were overlooked.

In the end, the court admitted that it was impossible to establish the truth, but awarded the Dei Gratia a salvage prize reduced to one-sixth of the ship’s value (approximately £7,400 instead of the £46,000 expected), an ambiguous decision that seemed to imply unresolved doubts.

The ship was returned to its owner, James Winchester, who hastily put it up for sale, beginning its reputation as a “cursed ship”. Flood’s investigation, rather than clarifying the mystery, further complicated it, burying crucial clues under a mountain of prejudice.

Had he followed more objective leads, such as the evaporation of alcohol in the red oak barrels or navigational error, we might have answers today. Instead, his incompetence became part of the myth, leaving the Mary Celeste at the mercy of legends and speculative theories for centuries to come.

What really happened on board the Mary Celeste?

The Mary Celeste represents the most perfect ‘cold case’ in maritime history, a puzzle whose pieces seem to belong to different pictures. Every element discovered on board tells a partial, contradictory story that defies any linear interpretation. Let’s analyse the key clues that have fuelled the mystery for over a century:

The mystery of the empty barrels

Of the 1,701 barrels of denatured alcohol, nine were found to be completely empty. Subsequent analysis revealed that these specific barrels were made of red oak (rather than white oak like the others), a more porous wood that could have allowed the contents to evaporate.

Experiments conducted in 2005 by the University of London showed that ethanol vapours (with a flash point of only 13°C) could have created an explosive atmosphere in the hold. But why were there no traces of combustion?

The missing lifeboat

The absence of a lifeboat suggests that the ship was abandoned voluntarily. Damage to the supports indicates that it was lowered quickly, not torn away by the storm. The 10-metre rope found hanging could be what remained of the connection to the mother ship, perhaps cut by friction or a knife. But why abandon a perfectly seaworthy ship?

Water in the hold

The 3 feet (about 1 metre) of water did not pose an immediate danger to a ship of that size. The dismantled pump could indicate an attempt at repair, but also an inspection to assess the extent of the water ingress. The sounding rod left on deck suggests repeated and concerned measurements.

Missing instruments

The disappearance of the sextant and marine chronometer (essential for navigation) along with the damaged compass could indicate that someone tried to take them away. Or that they were thrown overboard during some unexplained event.

Personal effects

The intact presence of valuables (the captain’s violin, Sarah’s jewellery, $3,500 in cash) rules out theft. But why leave behind what would have been essential in a lifeboat? The carefully stowed clothes contradict a hasty escape.

The logbook

The last entries on 25 November show no signs of alarm. But the absence of the following pages (torn out?) prevents us from knowing the final events. The discovery in 1991 of original notes by prosecutor Flood revealed that the ship had deviated north of its planned course.

The most credible theories:

- Panic caused by explosive vapours (the official theory): the vapours from the barrels convinced Briggs to evacuate temporarily, only to lose the lifeboat.

- Error of judgement: a combination of a faulty pump, defective instruments and bad weather led to the belief that the ship was sinking.

- Selective mutiny: only some of the crew rebelled, creating a chaotic situation.

- Natural phenomenon: a waterspout or underwater earthquake frightened the crew.

Unexplained details:

- Why leave the ship with so many supplies available?

- How can the total absence of signs of struggle or disorder be explained?

- Why were no bodies ever found, not even the remains of the lifeboat?

Every theory encounters at least one contradictory fact. Perhaps the truth lies in a combination of factors: vapours perceived as a threat, faulty instruments showing an incorrect position, a hasty decision that proved fatal. But without witnesses or definitive evidence, the mystery of the Mary Celeste remains as intact as the hull found that December of 1872.

Hypotheses and theories in detail

Over the course of 150 years, the mystery of the Mary Celeste has generated a kaleidoscope of explanations ranging from rigorous scientific analysis to the wildest popular fantasies. Among the most credible theories is the alcohol vapour hypothesis, supported by experiments conducted in 2005 by the University of London on the initiative of researcher Anne MacGregor. According to this reconstruction, the nine red oak barrels – more porous than the white oak used for the other containers – would have allowed the denatured alcohol to evaporate, creating a potentially explosive atmosphere in the hold. A possible “flash” without a visible flame could have frightened the crew, leading them to abandon the ship in a hurry. However, the absence of explosion damage or burn marks is a weak point in this otherwise convincing theory.

Other scholars, including MacGregor herself in collaboration with oceanographer Phil Richardson, favour a tragic navigational error amplified by faulty instruments. The marine chronometer, essential for determining longitude, would have provided incorrect data, leading Captain Briggs to believe he was 120 miles from his actual position. This, combined with the dismantled bilge pump and water in the hold, may have convinced the experienced sailor that the ship was sinking, prompting him to order the evacuation. MacGregor and Richardson’s reconstructions based on weather data from the time (taken from the ICOADS archive) show that the Mary Celeste did indeed deviate from its planned course, supporting this hypothesis.

There is no shortage of explanations linked to extreme natural phenomena, such as an encounter with a waterspout that would have terrified the crew without causing significant material damage, or a sudden tidal wave generated by an underwater earthquake, a phenomenon little understood at the time. Among the most intriguing but least plausible theories is that of ergot poisoning, a fungus found in rye that can cause hallucinations, although this does not explain why the crew members of the Dei Gratia who ate the same food were not affected.

The line between reality and fantasy becomes even blurrier with folkloric theories: from the attack of a hypothetical sea monster (disproved by the absence of damage to the hull) to imaginative alien abductions, popularised by an episode of Doctor Who in 1965 but obviously without any historical basis. Particularly ingenious, albeit completely false, was the hoax of Abel Fosdyk, a supposed survivor whose testimony, full of gross errors about the tonnage and composition of the crew, was published decades after the events.

The most widely accepted modern summary combines several elements: alcohol vapours perceived as an immediate threat, faulty navigation instruments, a malfunctioning pump and a sudden storm that may have separated the lifeboat from the mother ship. This scenario explains most of the clues, although some details, such as the apparently cut rope and the missing documents, continue to fuel the mystery. A chilling epilogue may have been provided by the discovery in 1873 off the coast of Spain of a lifeboat with five unidentified bodies, buried without anyone thinking to connect them to the Mary Celeste, adding a final, disturbing piece to a story already full of unanswered questions.

The fate of the Mary Celeste after its discovery and investigation

After the Gibraltar investigation, the Mary Celeste became a cursed ship, avoided by sailors and shipowners alike. James Winchester sold it quickly, but over the next thirteen years it changed hands seventeen times, each owner more unlucky than the last. Its sinister reputation made it unsellable until 1885, when its last owner, Captain Gilman C. Parker, attempted to deliberately sink it off the coast of Haiti to collect the insurance money.

The plan failed: the ship ran aground without sinking completely and Parker was discovered. Despite the fraud, the court acquitted him, perhaps influenced by the cursed fame of the Mary Celeste. Parker died mysteriously a few months later, while his partners ended up in an asylum and the other committed suicide, adding another dark chapter to the legend.

The wreck remained abandoned until 2001, when an expedition led by writer Clive Cussler identified it in the waters off Haiti. The ship was now reduced to a pile of timber, but its myth was more alive than ever. From a simple merchant brig, the Mary Celeste had become the archetypal ghost ship, its true fate lost between reality and legend.

The Mary Celeste in popular culture

The mystery of the Mary Celeste has become a cultural icon, inspiring novels, films, TV series and even video games. Its myth was born in 1884 with Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story “J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement”, which mixed fact and fiction, spreading the incorrect spelling “Marie Celeste” and introducing supernatural elements.

In cinema, films such as The Phantom Ship (1935) starring Bela Lugosi and Ghost Ship (1952) fuelled the idea of a cursed ship, while on television, series such as Doctor Who and Zaffiro e Acciaio imagined encounters with aliens and time travel. Literature and video games (such as Limbo of the Lost) have also taken up the story, often turning it into psychological horror, while researcher Anne MacGregor conducted an in-depth scientific investigation in the 2000s, resulting in the documentary ‘The True Story of the Mary Celeste’.

Today, the name “Mary Celeste” is synonymous with abandoned places and unsolved mysteries, even used in scientific contexts to describe inexplicable phenomena. The ship no longer exists, but its legend is more alive than ever, proving that some enigmas, rather than being solved, become timeless myths.

The mystery that never dies

After a century and a half, the Mary Celeste remains the archetype of the perfect maritime mystery. The combination of rational and inexplicable elements continues to fascinate.

The true power of this story lies in its incompleteness. The absence of bodies and definitive answers has turned it into a blank canvas onto which everyone projects their own fears and theories.

Perhaps, like all great mysteries, its value lies not in its solution, but in its ability to make us question the limits of human knowledge. While the wreck lies forgotten in the Caribbean, the legend of the Mary Celeste continues to sail undisturbed through time, proving that some stories do not need a conclusion to remain immortal.