Early 70s, Milan, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Catholic University of the Sacred Heart). These three elements – temporal and geographical – are enough to make a blood story a front page case. An unresolved case, an Italian cold case whose plot, weave and enigmas seem to be written, studied by a skilful screenwriter of mystery stories. A story worthy of a television series or a novel. The victim, however, is tremendously real.

Simonetta Ferrero, a career woman

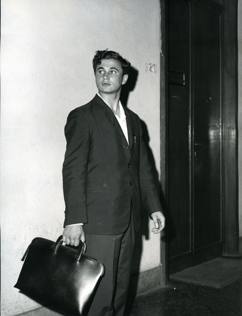

The protagonist of this crime story is Simonetta Ferrero. Born in Casale Monferrato in 1945 to a wealthy Piedmontese family but living in Milan, Simonetta embodies the classic career girl. Brilliant, scholarly, committed to voluntary work, ambitious but not self-interested, in the negative meaning of the term. Munny – her nickname – graduated in March 1969 from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Political Science.

Thanks to her precious knowledge and his father Francesco – a manager – Simonetta Ferrero joined Montedison (former Montecatini Edison), one of the most important and influential Italian industrial and financial groups. At the time, the Faculty of Political Science was headed by Gianfranco Miglio, a job he held for thirty years. The famous jurist, political scientist and politician was also an advisor to the President of Montedison itself, Eugenio Cefis (1971-1977). Simonetta, therefore, thanks to her qualities as well as to the undeniable internal ties of the company, is hired by Montedison as head of personnel. It was a demanding job that lived up to Simonetta’s ambitions.

Although she has a career, Simonetta lives with her family: her father Francesco, her mother Liliana (a housewife), her sisters Elena – a biologist at the State University – and Elisabetta, a graduate in Biology. A classic family. The classic beautiful family: present and Catholic parents, smart and educated -now with a high level job- daughters, a beautiful house in Milan, Via Osoppo. The uncle is Monsignor Carlo Ferrero, who will have the ungrateful task of celebrating the funeral of the poor Piedmontese girl in the parish between Via Osoppo and Piazzale Brescia.

Why, then, kill a woman like Simonetta Ferrero?

The Murder

The stages that mark the last hours of Simonetta Ferrero’s life and lead to the crime find their place in time on July 24, 1971. Simonetta has to do some chores, including something related to the upcoming trip to Corsica with her family: changing the Lire in Francs, the beautician, the perfumery, the tapestry, the purchase of an Italian-French dictionary. Carefree hours: the tram, Corso Vercelli, Corso Magenta, probably Via Carducci and Galleria Borella.

According to eyewitness accounts and receipts found on the crime scene, Simonetta Ferrero – around noon – is still alive. During this time, in fact, witnesses meet or see the girl in the above mentioned commercial activities and at the entrance of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart. It has never been clarified why Simonetta goes to the University on a Saturday morning, before a holiday.

The fact is that Simonetta will never come home. She is reported missing. In vain.

Simonetta was brutally killed inside the Milanese university.

The Finding

Simonetta Ferrero’s lifeless body was discovered on the morning of July 26, 1971. On a Monday. It was about 9 a.m. when the attention of Mario Toso, a 22-year-old seminarian and Philosophy student who was going to the secretariat of the Institute of Religious Sciences, was captured by an apparent loss of water from the women bathroom in block G. The young man stopped, entered the toilet and noticed that the door handle was covered in something sticky. It’s blood. There is also blood on the floor and on the door itself. When he enters the women’s toilet room, he first comes across the open sink, then Simonetta Ferrero’s lifeless body, with her head resting on her arm on the floor, on one side. Blood is everywhere: on the doors of the individual bathrooms, on the ground. Simonetta lies in the middle of the room, slightly off-centre and close to the window.

Toso, afraid, runs away. He returns to the seminary, at Mirabello Monferrato. The alarm for the finding of the girl is thus given by the caretakers and other students.

Simonetta has 33 wounds inflicted with a long and sharp cutting weapon (other sources indicate 44 stabs), seven of which were inflicted in vital areas. Neck, face and belly are mangled. The victim shows no signs of sexual violence. She is still dressed. Wounds on the palms of the hands indicate a strenuous defense by the girl. The analysis of the crime scene, in fact, outlines and describes a combative Simonetta, who tries in every way to escape and to struggle, despite being overwhelmed by the murderous fury of her killer.

Not only that: the blood stains (the fingerprint of a male hand) on the external side of the bathroom door – the one that, in essence, overlooks the corridor – and the blood stains on the floor at the door suggest that the killer (with hands, clothes and shoes certainly covered in blood) stops a few moments before leaving the toilet. A tall man: 1.80 m, probably even taller.

The individual is still, on the door: he wants to make sure that no one walks by in that moment and that no one has been attracted by the cries of help and pain of the girl. So, he wears clean clothes, he washes away the blood and comes out.

Who killed Simonetta Ferrero? And why?

Few clues, no culprits

This detective story contains a question that has never been answered in a certain and effective way: why was Simonetta at the University? And why was her in the bathrooms of block G, far from the entrance to the university building? Does Simonetta go to the university to retrieve some notes or just for mere physiological reasons, inevitable during an intense morning spent making the final preparations for the holiday in Corsica? Perhaps she had an appointment with another person who, then, will turn out to be his killer? Or perhaps, without her knowledge, she was followed by the killer himself until the tragic epilogue? It is not known.

Anyway, the investigative tracks reveal themselves, from the very first moments, to be weak and inconsistent. Mario Toso, although his position appears, at first, shaky and suspicious, is no longer under investigation: no clue against him, no evidence that he was on to the scene of the crime (accidental discovery of Simonetta’s body apart), no motive, no connection with the victim.

A robbery ended in tragedy? Even this option is promptly discarded: Simonetta still wears a gold ring on his finger and she still has all the money in his wallet: 3000 Lire and 300 French Francs.

Sexual violence? The doubt remains, although there are no clues in this regard. Yet, the cruelty of the crime cannot exclude the sexual or passionate murder of a raptus’ son. Finally, there are those who hypothesize a professional motive. Simonetta, in fact, had not hired some graduates from Montedison, discarding their resumes: a revenge for not hiring someone? A track, indeed, never supported by the investigations.

The police also investigates some individuals and “strange” students who are used to harass and provoke female students and commuting girls. Investigations, investigations, interrogations, testimonies, a great deal of chatter around Simonetta and the people who attend the Milanese university but nothing concrete that leads to the guilty person, the murderer. Years later, we will even think of a connection with the murder of Lidia Macchi, killed in January 1987 in Varese and whose profile is compatible with that of Simonetta. Hypothesis, however, suggestive but never confirmed.

Therefore, from the investigations, nothing emerges. Nothing at all. In 1993, an anonymous letter sent to the chief of police Achille Serra indicates a priest of the “Catholic University” as guilty. A serial molester. Also in this case, however, everything falls into a vacuum. It is the last, sudden reversal in a story that defining mysterious and not yet clear seems reductive.

It is 1971 and the investigation makes use of techniques – analysis of the crime scene, forensic pathology, criminal profiling, etc. – which today we would define obsolete or embryonic. For example, there is still no DNA test, an examination which, today, would perhaps have led to a name and surname and rewritten forever the fate of a rather intricate case.

The murderer of Simonetta Ferrero will probably never have a face or identity.

The result? The perfect crime.

Source of the photos: Corriere Milano