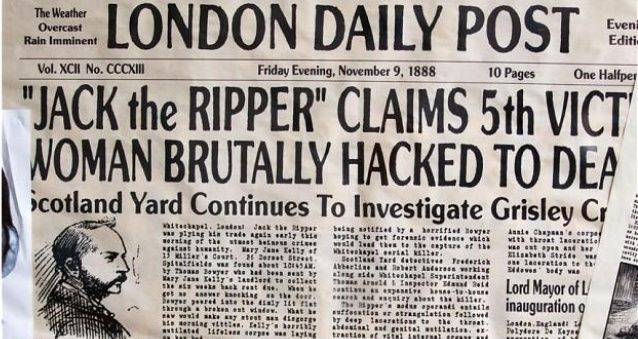

Jack the Ripper is the serial killer par excellence. His malicious charm transcends the ages, decades, centuries, reaching intact and enigmatic to present days. We are talking about Jack the Ripper, a serial killer who, between August 31, 1888 and November 9 of the same year, is the author of at least five crimes. Theatre of the murders, Whitechapel, infamous and degraded district of London passed to the chronicles and history just for the events related to Jack the Ripper. Even today, as we shall see, the murders attributed to Jack the Ripper are a real criminal puzzle for fans and scholars around the world: we can rightly say that we are facing the most famous “cold case” of contemporary history.

His indefinite identity adds mystery to mystery. Scholars, historians, criminologists, profilers, investigative journalists, scientists and simple enthusiasts ride and feed this mystery. Theories and hypotheses – more or less reliable, many of which are set only for sensationalistic purposes – follow one another and overlap over each other. It could not be otherwise: we are talking, in fact, about a crime that goes beyond the simple crime news. It is the “Holy Grail” of criminology, of the forensic sciences. Going into the deepest folds of the character Jack the Ripper is, undoubtedly, a boast, a success that appeals to many.

The ascertained victims

Five confirmed victims, then. However, historians and criminologists believe that Jack the Ripper has killed other times, perhaps sixteen. To understand Jack the Ripper, it is necessary to contextualize the historical framework within which he operates and to grasp, at least in the general and salient traits, the essence of the theatre within which the serial killer acts and moves: Whitechapel. We are in the late Victorian era; Queen Alexandrina Victoria – the last sovereign of the Royal House of Hanover – reigns firmly, on the throne of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, from 20 June 1837 (the date of the coronation is 22 June 1838) to 22 January 1901, the day of his death. The Whitechapel district is located in the so-called East End of London. In the Victorian era, Whitechapel was already for many years the seat of the – then considered – most infamous and outrageous work activities: slaughterhouses, tanneries, foundries. An ugly and squalid working-class neighbourhood, made up of farmers, workers, immigrants employed in small businesses and shops operating here, swarming with beggars and prostitutes.

Prostitutes

Yes, prostitutes. And so Jack the Ripper, in the implementation of his diabolical murderous plan, finds in the degraded neighborhood of Whitechapel the ideal stage on which to vent his murderous needs. A neighborhood that has a life of its own, where silence, crime and daily degradation coexist. A hunter of prostitutes, one might say. The five victims ascertained and attributed to Jack the Ripper, in fact, are five prostitutes. The modus operandi of “the Ripper” has gone down in history: he cuts his victims’ throats, then rages on the now lifeless bodies, mutilating them.

Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols Walker (43 years old, mother of five children had by her husband William Nichols, body found on August 31, 1888), Annie Chapman (46 years old, born Eliza Ann Smith, corpse discovered on September 8, 1888), Elizabeth Stride (date of discovery: September 30, 1888), Catherine Eddowes (also found on September 30), Mary Jane Kelly (body found on November 9, 1888) are the names of the five women certainly murdered by Jack the Ripper. All these victims are accumulated by the work, the prostitution, and, in fact, by the modus operandi with which they are brutally killed.

Mary Ann Nichols – whose body will be found at a slaughterhouse in Buck’s Row – presents the throat cut almost to the point of beheading, the intestines that have escaped and cuts to the genitals.

Annie Chapman – sposata con John Chapman, madre di tre figli, ritrovata presso il numero 29 di Hanbury Street – mostra la inconfondibile “firma” di Jack lo Squartatore: gola tagliata e quasi interamente recisa, ventre squarciato, intestini appoggiati sulla spalla destra, asportazione di vagina, utero e vescica.

Elizabeth Stride – whose body was found by a coachman in the then Berner’s Street – has the typical, deep throat cut but no mutilations. Probably, the arrival of the coachman at the crime scene means that “the Ripper” cannot complete the ritual.

This unforeseen event is probably the cause of the – so to speak, “unplanned” – killing of Catherine Eddowes, found dead in Mitre Square. The ritual against the body of the Stride, in fact, had not been completed: another victim is needed. The ferocity and frustration of Jack the Ripper against the Eddowes are perceived in all their strength: body (like the other victims) in a supine position, throat, as always, cut almost to the point of beheading, the face disfigured by cuts and mutilations. The nose and lobe of the left ear are severed, as also the eyelid of the right eye. The gums are visible through the deep cuts to the lips. The body is furrowed by a single gash that goes from the throat to the genitals. Like Annie Chapman, Catherine Eddowes also has her intestines resting on her right shoulder. The liver was showing through the cuts, the left kidney and the genitals are removed.

But it is with Mary Jane Kelly that Jack the Ripper reaches the apex of his own lucid murderous madness. The reddish-blonde haired woman is found dead in her own bed; the woman is staying in a small apartment for rent, at 13 Miller’s Court, near Dorset Street. The body will be discovered by the landlord’s assistant, who has come to collect weeks of rent arrears. The throat has the proverbial, deep cut close to beheading, the face is heavily mutilated, abdomen and belly – mutilated – open but now deprived of many organs, many of which scattered near the body and in the house. The liver is placed by Jack the Ripper between the legs of Mary Jane Kelly, the intestine in his hands. The heart is not found at the crime scene, which has given rise to two hypotheses: the first sees Mary Jane Kelly’s heart simply burned in the fireplace, the second, far more disturbing, would be that the heart was cooked and eaten by Jack the Ripper himself. However, Colin and Damon Wilson in “The Great Book of Unresolved Mysteries,” state that the woman’s heart rests on the pillow, near the head.

Seven “indecipherable” victims

There are at least seven other possible victims attributable to Jack the Ripper. Indeed, there is no factual, investigative or criminological certainty about these crimes. Experts and scholars have never been able to reveal, in a clear and irrefutable way, the connection between the aforementioned seven murders and the serial killer of Whitechapel. Often, in fact, these are crimes that present confused and faded similarities with the known and unmistakable modus operandi of Jack the Ripper. In only two cases – that is, those related to the murders of Martha Tabram and Frances Coles – the opinions seem to converge, to indicate and confer an attribution (still shy but without doubt plausible) of both victims to Jack the Ripper.

Here, then, is a brief ID of the seven victims in question: two women without identities murdered and found respectively on December 26th, 1887 and September 10th, 1889, Emma Elizabeth Smith (45 year-old prostitute, attacked by three men on April 3, 1888, wounded in the perineum and died, later, of peritonitis), Martha Tabram (39 year-old prostitute found dead on August 6, 1888, presents cuts in the lower part of the body inflicted by two different weapons), Rose Mylett (December 20, 1888, presents signs of 39 stabs), Alice McKenzie (40 year-old prostitute, found dead on July 17, 1889; the woman has two cuts, or perhaps stabs, in her throat and abdominal mutilations, smaller than the canons of “the Ripper”), Frances Coles (a 26-year-old prostitute, found still alive on February 26, 1891 by a patrolman at Chamber Street; the woman dies shortly after. The Coles presents three wounds to the throat – two of which from left to right – and a wound in the back of the skull).

Marta Tabram and Frances Coles, therefore, are indicated as possible, likely victims of Jack the Ripper. That is why it is possible to find these two women, in the amount of documentation available around the murders of Whitechapel, in the list of official victims attributed to Jack the Ripper. In the case of Frances Coles, it is thought that the agent – hearing suspicious noises and seeing a man move away quickly from the place where the woman was found, from Swallows Gardens in the direction of Mansell Street – unintentionally frightened the Ripper, intent on performing the ritual of death on the body of the young unlucky woman. A circumstance already experienced in the case of the murder of Elizabeth Stride, when, that is, the serial killer is frightened by the passage of the coachman and runs away.

The letters

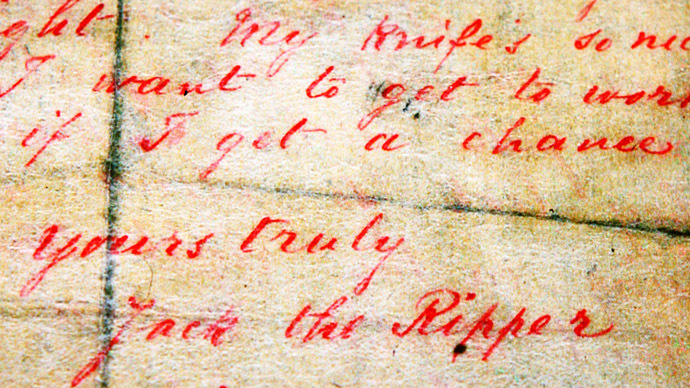

Jack the Ripper represents, to this day, the prototype of the serial killer: an unmistakable modus operandi, a macabre ritual to characterize in a systematic and unique way his own “deeds”, elusive, with a thousand hypothesized identities, none of which really and concretely confirmed. The letters, in this sense, increase the halo of mythology that weighs around the figure of Jack the Ripper. During the course of the bloodshed linked to the serial killer of Whitechapel, investigators and newspapers receive thousands of letters: mythomaniacs who pass themselves off as the killer, more or less useful testimonies in order to trace a profile and follow precise investigative tracks. A multitude of letters which, however, are almost always of little or no importance. Three letters, however, capture the attention of the investigators. Letters which, still today, are the subject of in-depth studies and at the centre of the intricate debate around Jack the Ripper. Through these letters, Jack the Ripper challenges the police, Scotland Yard and the press: strong of his evanescent and elusive position and of his own “enterprises” which are sowing panic and keeping the investigators nailed, the serial killer almost irksome those who hunt him down.

The first letter worthy of attention is dated 25 September 1888: it has been renamed “Dear Boss Letter”. The letter was sent to the Central News Agency, which received it on 27 September. The news agency then forwards the document to Scotland Yard.

Here is the full text:

25 Set. 1888.

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

PS Wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now. ha ha.

With “The Saucy Jack postcard” of October 1, 1888, the register of the challenge definitely changes tone: it becomes more intense, as concise as it is meticulously gruesome. In this postcard, in fact, the alleged serial killer refers to the death of two women, a notorious “double event”: is it the double murder of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes? Here, in fact, the Ripper seems to describe the dynamics of the two murders just mentioned; details that only the killer could know. A very precise event, a very detailed dynamic, peculiarities that lead to believe that it is really Jack the Ripper the author of the text below reported in its entirety.

I was not codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip, you’ll hear about Saucy Jacky’s work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. Had not got time to get ears off for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again. – Jack the Ripper

During and after the murders of Whitechapel, investigators and the press reject the theses about the authenticity of the “Dear Boss Letter” and “The Saucy Jack postcard”. Even today, scholars and enthusiasts have not found a common meeting point, dividing themselves into two camps: those who support the authenticity of the letters, those who, on the contrary, believe they are well-designed forgeries.

The “From hell letter” is the last, disturbing letter probably attributable to Jack the Ripper. It was received on 16 October 1888 by George Lusk, head of the Whitechapel supervisory committee.

From hell.

Mr Lusk,

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

signed

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk.

Unlike the other two letters, this does not bear the signature of “Jack the Ripper”. However, even the “From hell letter” shows marked similarities with the other two letters. Starting with the style in which it is written and the spelling mistakes: a man of poor culture or a highly educated person, so as to deliberately insert the errors and write the words according to the pronunciation, so as to mislead the investigators? It is one of the many riddles still unsolved. And that’s not all. The letter is, so to speak, accompanied by a box containing half of a human kidney, stored under alcohol. It is thought to be Catherine Eddowes’ kidney but, even in this case, opinions are divided: between those who support the authenticity of the document and the attribution of the kidney to the Eddowes and those who, instead, confirm the track of the umpteenth joke, even the mystery that surrounds the “From Hell letter” is far from being clarified. Currently, there is only the original “Dear Boss Letter“: first stolen from the archives of Scotland Yard, then returned in 1988. Of the other two letters, also stolen from unknown people and never retrieved, there are only photographs and facsimiles.

Who is Jack the Ripper?

The story of Jack the Ripper, as can be seen, is composed of many facets. An intricate sequence of crimes deciphered only in part, a ritual modus operandi that leaves open to multiple interpretations, enigmatic letters of authenticity yet to be confirmed and, above all, an identity yet to be revealed. Who is Jack the Ripper?

Tracing the profile of Jack the Ripper is, without a doubt, an operation that has kept and still keeps occupied the non plus ultra of the specialists in the field, the best profiler in the world, from those of Scotland Yard to the counterparts of the FBI. The criminal profiling – currently in the limelight thanks to the numerous TV series dedicated to it – is a mixture of science, art and intuition, an essential tool in the hands of investigators so that any forensic investigation can be pointed in the right direction. The profile is the result of several factors, from the scrupulous analysis of the crime scene in its entirety to the study of the modus operandi, “trademark” of any serial killer.

On October 25, 1888, Robert Anderson – Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police – instructed Dr. Thomas Bond, English surgeon, Fellowship of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons and Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery, to write a profile of Jack the Ripper. This is, to all intents and purposes, the first documented case of criminal profiling in history. Anderson sends Bond the documents relating to the murders of Nichols, Chapman, Stride and Eddowes. In the meantime, Mary Jane Kelly is killed, whose autopsy will be performed by Dr Bond himself. When Dr Bond mentions “Dorset Street,” he refers to Mary Jane Kelly’s crime scene. On November 10, 1888, Bond replied to Andesron, sending him the following report.

“I beg to report that I have read the notes of the 4 Whitechapel Murders viz:

- Buck’s Row.

- Hanbury Street.

- Berner’s Street.

- Mitre Square.

I also performed an autopsy of the mutilated remains of a woman found yesterday in a small room on Dorset Street.

- There is no doubt that all five murders were committed by the same hand. In the first four, the gorges seem to have been cut from left to right. In the latter case, because of the wide mutilation, it is impossible to be precise on the direction of the deadly cut, but arterial blood spatters were found on the wall near where the woman’s head was supposed to be.

- All the circumstances surrounding the murders lead me to believe that the women were in a supine position when they were killed and that, in all cases, the first shot was inflicted on the throat.

- In the four murders of which I have only read the testimonies, I cannot form a very precise opinion about the time that elapsed between the murder and the discovery of the body. In one case, that of Berner’s Street, the discovery seems to have taken place immediately after the fact. At Buck’s Row, Hanbury Street and Mitre Square, it is likely that only three or four hours have passed. On Dorset Street, the body lay on the bed when I arrived at two o’clock, and was completely naked and mutilated, as I reported in the attached report. The rigor mortis, which had already begun, progressed during the exam. Because of this, it is difficult to report, with any measure of certainty, the precise time elapsed since death, as this period varies from 6 to 12 hours before the start of rigidity. At two o’clock, my body was relatively cold and I found the remains of a recent meal in my stomach and intestines. It is therefore almost certain that the woman must have been dead for about 12 hours and the partially digested food indicates that the death occurred about 3 or 4 hours after ingestion. Consequently, it is likely that the time of the murder should be between one and two in the morning.

- In all cases, there is no evidence of a struggle: the attacks were probably so sudden and carried out in such a way that the women were unable to resist or shout. On Dorset Street, the corner of the sheet to the right of the woman’s head appeared very torn and full of blood, a sign that perhaps the face was covered by the sheet at the time of the attack.

- In the first four cases, the killer probably brought the assault to the right side of the victims. On Dorset Street, it is likely that the attack was carried from the front or the left, since there was no room to strike between the wall and the part of the bed on which the woman lay. As already reported, blood was spilled on the right side of the woman and splashed on the wall.

- The blood may not have splashed or wet the killer, but it is likely that he spilled on his hands and arms and stained part of his clothes.

- In all cases except Berner’s Street, the mutilations were all of the same type and clearly showed that in all murders, the aim was to mutilate the victims.

- In all cases, the mutilations were inflicted by an individual without scientific or anatomical knowledge. In my opinion, the killer does not even have the technical knowledge of a gravedigger, a horse slaughterer or someone accustomed to shredding dead animal meat.

- The weapon is probably a solid knife at least 15 centimeters long and three centimeters wide, very sharp and pointed. Probably a greenhouse knife, butcher’s knife or a surgeon’s iron. Almost certainly an unbent knife.

- The killer is probably a physically strong man of great coldness and audacity. Nothing indicates that he had an accomplice. In my opinion, he is a man subject to periodic attacks of murderous and erotic paroxysm. The type of mutilation inflicted indicates that the subject may be in a sexual condition defined as satiriasis. It is of course possible that the homicidal impulse may have its origin in a vindictive or remorseful mental condition, or that the original illness is a religious mania, but I do not think either of these two hypotheses are probable. It is very likely that the killer appears externally harmless and calm, perhaps middle-aged and dressed in an orderly and respectable manner. I think he usually wears a cloak or overcoat, otherwise he would hardly have been able to fail to attract attention on the street if the blood on his hands or clothes had been visible.

- Giving as assumed the description of the murderer just given, it is likely that he is a lonely man with eccentric habits, who does not have a regular job but who perhaps enjoys a small income or a pension. He may live among respectable people who have some knowledge of his character and habits and who may have reason to suspect that he is sometimes unsound in mind. They may not be willing to report their suspicions to the police for fear of trouble or over-exposure, while the prospect of a reward would allow them to overcome all scruples.

Best regards

Thomas Bond”

There is therefore a reference to an apparently harmless man, well-dressed, physically gifted, affected by – according to a medical terminology used in the past – satiriasis, a sexual pathology indicating a morbid increase in male sexual instinct, now called hypersexuality. Bond excludes that Jack the Ripper could be a surgeon or a butcher, an opinion matured through the analysis of the mutilations and cuts made to the victims. Yet, a modern criminal profiling of the FBI speaks of a possible butcher or even an assistant to a doctor, aged between 28 and 36 years. Is it likely that a person not competent in anatomy and surgery could have practiced the proverbial mutilations – very precise – inflicted on the victims? Questions which, even today, deserve attention.

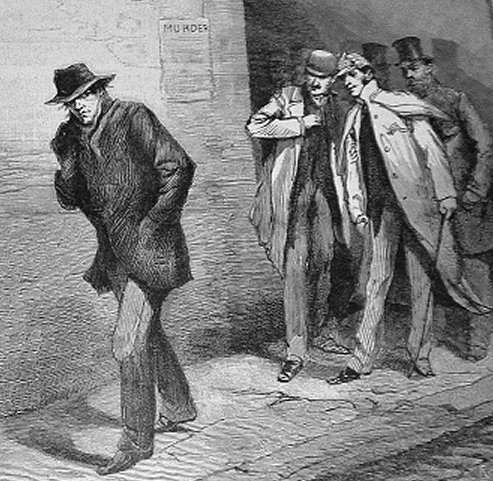

It is evident: the real identity of Jack the Ripper is far from being deciphered. It is not by chance that conjectures about the identity of the serial killer in London abound, in an uncontrolled whirlwind, stimulating but often redundant and bizarre, of names, profiles, suspects, studies aimed at revealing the real face of the murderer, grand scoops (or presumed such) that follow one another punctually and that “finally-unveil us-the-real-identity-of-Jack the Ripper”. So many theories, so few certainties. It is precisely this perennial and chronic branching in the dark that has fed and nourished, already from that distant but still current 1888, doubts, mystery and even satire around the news of Jack the Ripper and the work of the London police. Punch – a pungent weekly of English satire active between 1841 and 1992 and from 1996 to 2002 – in the dark days of that fateful 1888 underlines, in an ironic key, the inability of investigators to identify and stop the serial killer of prostitutes.

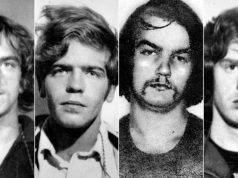

The suspects: many names, few certainties

From the very beginning, investigators understand that capturing the serial killer is a difficult task. During the investigation – and in the years immediately following the murders of Whitechapel – police and Scotland Yard question numerous people, including witnesses, local people and potential suspects. A laborious activity which, however, will be vain. No one will ever be convicted for the murders of Whitechapel. The day after the murder of Annie Chapman, John Pizer (or John Piser), a Polish craftsman at a leather workshop, is arrested. The locals blame the Polish, nicknamed “leather apron”, but the leather apron found near the crime scene does not belong to Pizer. The latter will be released a few days later.

A similar fate, in 1891, was due to James Thomas Sadler, a friend of Frances Coles, a dubious – but probable – victim attributable to Jack the Ripper. Sadler is arrested for the murder of the woman but the lack of evidence will cause the man to be soon released.

In the cauldron of the suspects, invariably, have also ended up illustrious characters, starting with Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde (better known as Oscar Wilde) and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, in art, Lewis Carroll. The latter is cited, on the basis of some anagrams, by the writer Richard Wallace as guilty. However, this leads are unlikely and imaginative.

The “royal plot”: suggestion or truth?

Then there is a rather evocative lead, which leads to his British Majesty. This lead, to this day, is synonymous with conspiracies and cover-ups designed to hide unspeakable truths. This is the thesis, for example, embraced by the movie “From Hell”, a 2001 film directed by the brothers Albert and Allen Hughes, inspired by the graphic novel of the same name by Alan Moore. This theory, intertwined with Freemasonry, has as its protagonist a Masonic doctor, Jack the Ripper, in charge of killing according to specific rituals all the witnesses of the Catholic marriage between Albert Victor Christian Edward Duke of Clarence and Avondale – a member of the English royal family and grandson of Queen Victoria – and a prostitute of Whitechapel, a relationship from which a daughter is also born. Legend, truth? Of course, the heir to the throne Albert Victor is not in London during the murders: historical documents, in fact, attest to his absence from the capital of the United Kingdom. So, without a doubt, Queen Victoria’s grandson is not the material perpetrator of the crimes. There remains a question mark. What if he was the instigator of the murders? A tickle but never proven and perhaps never demonstrable hypothesis. Historians believe that the so-called “royal conspiracy” is a hoax, an urban legend resulting from misunderstandings, false historians and false testimonies.

William Withey Gull

Another notable defendant is William Withey Gull, Queen Victoria’s personal physician. The renowned man of science is brought up by Joseph Sickert, son of the German painter Walter Richard Sickert. This theory, in essence, is a further interpretation of the “royal conspiracy”. Gull, in fact, according to this hypothesis, would be the material perpetrator of the crimes attributed to Jack the Ripper: a doctor, skilled with the tools and instruments of the trade, a coachman as an accomplice, John Charles Netley. Murders, according to the theses of the “royal conspiracy”, aimed at eliminating uncomfortable witnesses who knew about the birth of an illegitimate heir to the throne. At the time, Gull was a 72-year-old man. He will become disabled due to a stroke, an event that comes at the same time as the end of the murders at Whitechapel. Just a coincidence? Truth, legend? Again, certainty does not exist. Bond, in his 1888 report, ruled out the possibility that the murderer might be a doctor, yet some clues seem to provide a basis for the trail leading to Gull.

Sir John Williams

Sir John Williams is the last figure linked to the British Royalty. In reality, he is not involved in the enigmatic “royal conspiracy”, but would act in a completely independent and autonomous way. Williams is the midwife of Princess Beatrix of Saxony-Coburg-Gotha, the last daughter of Queen Victoria. Williams, according to a first theory, personally knows all the victims and kills women in the (vain) attempt to understand the causes of infertility. A second hypothesis, Williams wants to kill women because his wife, Lizzie, can not have children.

Everyone is guilty, noone is guilty.

Ironically, it is Walter Richard Sickert – the aforementioned German painter – who is at the centre of a controversial hypothesis. According to the writer Patricia Cornwell, Jack the Ripper is Walter Richard Sickert. This “verdict” is sanctioned by the 2002 book, “Portrait of a Murderer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed”, in which the famous American writer develops a personal investigation path that had never been considered before, but, at the same time, was not accepted by historians. A meticulous, detailed, complex analysis, suitable for all the most modern techniques of forensic research (including DNA testing) but, according to experts and scholars, not convincing. Who is right, Patricia Cornwell or her detractors? Maybe we’ll never know.

Joseph Barnett

Joseph Barnett is, according to many, a very interesting suspect. But even his position, as we shall see, is far from being defined and outlined with rigor. Barnett is Mary Jane Kelly’s lover and partner, the last known victim attributable to “the Ripper”. The relationship between the two took place between the spring of 1887 and the end of October 1888. The testimonies of the time give us a violent man, humble (he is a former fishmonger), frustrated, disappointed by the behavior of Kelly, who returned to prostitution after he lost his job. At the time, Frederick George Abberline – a policeman active in the investigation of Jack the Ripper, and also a leading (and fictionalized) figure in the aforementioned film “From Hell”, in which he is played by Johnny Depp – repeatedly questions Barnett, but for lack of evidence he will never be charged. There are several hypotheses on the table. The first one wants Barnett to have killed only Mary Kelly, imitating the real murders attributable to the Ripper. After all, Mary Kelly was killed at home: only the woman herself and Barnett had the keys. We also know that Barnett visits Mary Kelly on the evening of November 8th, before leaving around 8:00 p.m. A second hypothesis tells of a Barnett who, as a sign of revenge and retaliation against Kelly, kills other prostitutes. Some clues seem to identify Barnett with the real Jack the Ripper, others, on the contrary, deny this certainty. Above all, an enigmatic address noted on an envelope of a letter sent by the alleged Ripper: “M Sp 26”, that is Miller’s Court Spitalfields 26, the address of Barnett. Is Barnett the real Jack or is the real Jack who framed Barnett through the address maliciously affixed to the letter? Barnett’s position, therefore, also oscillates between myth and reality.

George Hutchinson

Other sources lead to additional profiles and suspicions. George Hutchinson, an unemployed worker who lives near Mary Kelly’s house, testifies to having seen the killer with Kelly. A very detailed description. All too detailed: he, in fact, claims to have seen the killer at 3 a.m., in the dark. Abberline, however, thinks the witness is reliable. Some scholars, however, identify Hutchinson as the Ripper. Some serial killers, in fact, are used to participate in the investigation, blending themselves with the unsuspected. Not only that: American newspapers of the late nineteenth century tell of a certain George Hutchinson, protagonist in Chicago of a murder against a woman with the modus operandi of Jack the Ripper.

Charles Allen Lechmere

Charles Allen Lechmere is one of many “suspects”. A delivery boy and coachman at Whitechapel, according to some scholars he has all the requirements attributable to the profile of Jack the Ripper. His position is rather precarious: he is the first to find the body of Mary Ann Nichols, provides investigators with a false address, false testimony, works as a coachman and messenger (also transporting meat) in the very places where the serial killer acts. According to the Swedish investigative journalist Christer Holmgren, Lechmere first kills Tabram, then the other five canonical women. He also attributes to Lechmere the murder of the headless woman, whose mutilated trunk is found in the Thames. Seven victims.

Thomas Neill Cream

Thomas Neill Cream, a surgeon specializing in clandestine abortions, comes into play because of his alleged declaration at the point of death. Natio of Glasgow, Scotland, moves and operates between London, Canada and Chicago. We are talking about a serial killer, renamed “Lambeth’s Poisoner”. Finally captured after numerous vicissitudes, Cream was sentenced to death (hanging) on November 15, 1892, at the London prison of Newgate. According to his executioner, James Billington, it seems that Cream, just before he died, said this words: “I am Jack the…”. Suggestion, invention or truth? Probably the first two. Cream, in 1888, was in prison in the United States, where he remained from 1881 to 1891. Conspiracy theories say that he fled prison, bribing agents and guards. But, in fact, these are fanciful conjectures, however, denied by many reliable people.

Doubts and conjectures that also affect the figure of Thomas Hayne Cutbush, a student in medicine with syphilis. Psychologically unstable, he was admitted to the Broadmoor Hospital in 1891, where he remained until his death in 1903. He is the author of an attack on a girl, is also a suspect in the murders of Whitechapel but nothing more. Too few elements to incriminate him, yesterday as 129 years later.

Frederick Bailey Deeming

Frederick Bailey Deeming is an additional assassin identified as Jack the Ripper. In 1891 he kills his first wife – Marie -, his four children and his second wife, Emily Mather. On 23 May 1892, in Australia, he was executed: hanged. Probably, almost certainly, Deeming is not the Ripper, but some contemporary newspaper articles to his death sentence, speculations of various kinds, imaginative poetic verses and his death mask shown, in the Scotland Yard Museum of Crime, as the face of Jack the Ripper have fueled and continue to fuel the belief that Deeming is indeed the Ripper.

Not only murderers

Even a writer and journalist such as Robert Donston Stephenson can end up on the list of suspects. Passionate about black magic and occultism, Stephenson develops rather personal theories about the identity of the Ripper. During the Whitechapel murder period, Stephenson was at the London Hospital: he was here exactly from 26 July to 7 December 1888. He showed an intense interest in the murders of Whitechapel, considering the nature and modus operandi that characterize the crimes themselves. The story is clamorous: Stephenson goes from accuser to accused. After having elaborated, in fact, his own theory – the killer is an expert in black magic, occultism and kills for ritual purposes -, he will be accused of being Jack the Ripper. This enormous misunderstanding stems from the conjectures initially prepared by the publisher William Thomas Stead, Baroness Vittoria Cassini Cremers and Aleister Crowley, theories resumed later and further inflated and fictionalized. But the facts and the orthodox testimonies exonerate Stephenson.

James Kelly (murderer of his wife in 1883; cuts her throat) and Alexander Pedachenko are proof that everyone can fall into the “trap” of the suspects. The former, although he has killed, is accused, especially in recent years, by authors of books and TV programs on the basis of scarce and undocumented evidence. The second, it seems, is an invented character, born from the imagination of William Le Queux. He claims to have read some of Rasputin‘s memoirs. According to the resounding revelation of Le Queux, the self-styled active healer of the Tsars of Russia indicates in the name of Alexander Pedachenko the real Jack the Ripper. Pedachenko would be a Russian psychopath doctor, officer of the Okhrana, the Tsarist secret police. The purpose of the murders it’s to discredit Scotland Yard. Pedachenko acts together with two trusted accomplices: the imaginary “Levitski” and the equally imaginary Winberg, a tailor. A completely unfounded cartoon-like story.

The conjecture that accuses James Kenneth Stephen, poet and guardian of Prince Albert Victor, is also unfounded. It all comes from a lead traced by Michael Harrison, who, in 1972, glimpsed in Stephen the possible Ripper. Misogynist, jealous of Albert Victor’s women’s companies, begins to take revenge by killing prostitutes. According to Harrison, moreover, his handwriting is very close to that found in the letter “from hell”, attributed to the Ripper. In subsequent years, these conjectures will be resumed and further elaborated, in a crescendo of sensationalistic theories but historically very unreliable and unconvincing.

The list of suspects – few official ones and many, perhaps too many, which are the result of suggestive conjectures but without any concrete foundation – is long and, at almost regular intervals, enriched with new names and elements.

Official suspects

Montague John Druitt is the first official suspect. A wealthy lawyer, he was found dead on December 31, 1888, probably suicidal. The death of Montague John Druitt and the end of the Whitechapel crimes are, for Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten (Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police), sufficient coincidences to suggest that the lawyer could be Jack the Ripper.

Seweryn Antonowicz Kłosowski, better known as George Chapman, is a Polish surgeon who emigrated to London between 1887 and 1888. Here, he changed his name to George Chapman. In 1902, he is accused of the murder of his self-styled wife, Maud, and of the two, equally self-styled, previous wives, Mary Spink and Elizabeth “Bessie” Taylor. These crimes – antimony poisoning – were committed between December 1897 and February 1901. “George Chapman” was sentenced to death in 1903. According to Abberline, Jack the Ripper is Kłosowski . In reality, this hypothesis seems unlikely. Kłosowski is a violent man (his real wife, Lucy Kłosowski, suffers acts of cruelty and threats from her husband), but the modus operandi is diametrically opposed: Kłosowski kills poisoning his victims, Jack the Ripper cuts his throat and mutilates the bodies according to a dark but blatant ritual made of blood and brutal fury.

The “Polish strand” also contemplates Aaron Kosminski. In 2014, a series of articles published in the main Italian and international newspapers highlights the sensational news: Aaron Kosminski is Jack the Ripper. What is true? Let’s proceed with order. The figure of Aaron Kosminski emerges since 1888, the year in which Jack the Ripper rises to the forefront of the news. He is a Polish barber of Jewish origin, with psychotic behaviour (he was admitted, in 1891, to Colney Hatch’s asylum), afflicted by compulsive masturbation, hallucinations and schizophrenia. From Colney Hatch he was transferred to the asylum of Leavesden, where he died in 1919. Kosminski, at first, enters the story of Jack the Ripper as a barber active in Whitechapel, also plagued by numerous psychological and sexual disorders. A barber, then, with knives and a leather apron, similar to the one that will be found next to the body of the Eddowes. Secondly, Kosminski is considered the author of some documents related to the events of Whitechapel: the letters attributed to Jack the Ripper, finally the inscription found in a crime scene that reads “the Jews are those who will not be accused at all”. Recently, Kosminski’s character has returned to the forefront. The credit goes to Russell Edwards, author of the book “Naming Jack the Ripper“. According to Edwards, Jack the Ripper is Aaron Kosminski. The evidence lies in a shawl that belonged to Catherine Eddowes, bought at an auction by Edwards in 2007, never washed and still showing traces of blood and sperm. The evidence of mitochondrial DNA – through comparisons with their respective descendants – would have confirmed both the shawl’s belonging to Catherine Eddowes, and the presence of Aaron Kosminski at the scene of the crime. Are this book and this evidence (contested with further scientific and historical evidence by other experts) sufficient to establish the identity of Jack the Ripper and close the case 129 years later? Are Aaron Kosminski’s profile and personality compatible with the Ripper’s modus operandi? Is the finding of the alleged shawl that belonged to Catherine Eddowes just a clever advertising move?

In this magma of suspects, other characters emerge, whose stories we will briefly analyze. The dribbling between official suspects and those resulting from conspiracy fantasies, investigations by journalists, historians, forensic scientists and simple criminology enthusiasts is unique and strongly characterizes the case of Jack the Ripper. It’s like watching a play: the characters enter the scene and then go out and enter again. Each character carries stories, doubts, suggestions, fantasies, skeletons in the closet, truths and legends.

James Maybrick is one of the many characters who participates in this virtual show. Maybrick is a cotton merchant from Liverpool: he would have killed the five women out of jealousy and revenge against his wife, Florence, who will also be charged for the murder (arsenic poisoning) of James himself. A motive, indeed, shaky and unconvincing. If he were still alive, he could probably denounce his slanderers for defamation, winning the lawsuit as well. It all began in the early 1990s, when Michael Barrett published a diary of Jack the Ripper’s confessions. A few years later, Barrett and his wife admit and confess: it’s a forgery. Then, they retract, affirming the authenticity of the diary. In reality, it is a forgery and the fact that the Barrett couple (even after the divorce…) have repeatedly chinched about the real truth of the document in question is one of the clues that leads to believe that it is a forgery.

Robert Mann is another individual on several occasions pointed out as guilty of the murders of Whitechapel. Assistant to Whitechapel’s morgue, he allegedly killed seven women, from Martha Tabram to Alice McKenzie. We know very little about Robert Mann, indeed. However, some experts consider Mann consistent with the profile of Jack the Ripper, although the few testimonies do not perfectly match.

Carl Ferdinand Feigenbaum is a merchant sailor. In 1894, he was arrested in New York for the murder of Juliana Hoffmann, a crime that earned him the electric chair: the execution is dated April 27, 1896. The day after his execution, the assassin’s lawyer, William Sanford Lawton, declares that Carl Ferdinand Feigenbaum is Jack the Ripper. Apparently, Carl Ferdinand Feigenbaum was the author of a blood trail from 1891 to 1894: from the USA to Germany, passing, of course, through London and Whitechapel. This theory also creaks: other historians and scientists reject this thesis.

Michael Ostrog, Russian, is another character probably wrongly accused of being the Ripper. Thief, mythomaniac, often changes identity: he skillfully juggles the art of fiction. Macnaghten has been investigating the Russian figure since 1889, but the clues against Ostrog are scarce and low-profile. Currently, historians tend to remove Ostrog from the list of suspects.

Much more substantial – but historically unsupported – are the clues that lead to Francis Tumblety. Of Irish origin, Francis Tumblety is a trader of medicines and herbs, but he usually pretends to be a doctor. He marries a prostitute, shows misogynist attitudes, is arrested for homosexuality in 1888, involved (but then cleared) in the murder of Abraham Lincoln. In short, a ubiquitous all-rounder in the borderline news. He lived in France and the United States, where he had an unusual and macabre collection of uterus. In general, his profile has traits in common with those of the Ripper, but even Francis Tumblety has doubts. Some scholars claim that the bizarre Irish trader is the real Ripper: the author of the first four murders, but not of the brutal murder of Mary Kelly.

William Henry Bury is the last character we’re going to mention. Bury went down in history for being the last to be sentenced to death in Scotland, in Dundee. It was on 24 April 1889. Bury was sentenced to death for the murder of his wife, Ellen Elliot, who was probably a former prostitute and with whom he had a very troubled relationship. William Henry Bury kills his wife in a manner only similar to the typical modus operandi of the Whitechapel Ripper: Ellen’s body, in fact, presents numerous wounds to the abdomen, a sign of a fury postmortem by her husband. The woman’s body is placed inside a crate. Soon the truth is reached and Bury is indicted, tried and finally executed.

Bury admits to the murder of his wife, but denies that he is Jack the Ripper. Yet, Bury is a serious suspect, although – as in other cases analyzed here – his history, his movements and his profile do not exactly match the canonical criminal identikit of the Ripper.

The wounds inflicted on his wife’s body, the fact that, between October 1887 and January 1889, he lived in Bow, near Whitechapel, the articles published by the daily newspapers “The Dundee Advertiser”, “The New York Times” and “The Dundee Courier” in which Bury is openly accused of being the Ripper, the books and articles published in the early decades of the twentieth century in which they continue to support this thesis and other oral testimonies far from being verified make it possible that, for several years, Bury is described as a possible author of the crimes of Whitechapel. The factual reality, however, explicitly tells us other truths: Ellen is strangled with a rope, the wounds inflicted on his body have different characteristics from those found on women killed by the real Ripper. In addition, Bury confessed to a murder, which is by no means negligible: would the real Jack the Ripper have ever confessed to his murders? We strongly doubt it.

The Legacy of Jack the Ripper: 129 Years of Mythology

The story of Jack the Ripper has taken on, in many years, the appearance of a sort of mythological tale of terror. Truth and legend collide, meet and intertwine seamlessly.

Historians, experts of various kinds and simple enthusiasts have, involuntarily but often consciously, contributed to the drafting of this virtual tale of terror. Theories and conjectures, even the most imaginative, have made the case of Whitechapel’s serial killer even more famous. As already said at the beginning, the most famous “cold case” in contemporary history.

Jack the Ripper, probably, will never be discovered: he was not caught alive, probably he will never be discovered dead. However, even in the face of the most meticulous and scientific of modern investigations, there would always be a halo of doubt for 129 years. A posthumous condemnation impossible to verify and confirm in an incontrovertible, definitive and complete way. In short, it is impossible to put the words “end” on this intriguing and intricate case.

In particular, it is Jack the Ripper’s modus operandi that has fuelled hypothesis, conjecture and mythology. Jack is not a simple (so to speak) serial killer, it’s something more. He is an authentic artist of evil, impersonating the sublimation of evil. Impossible not to fantasize about his murders, about that macabre and surgical ritual that distinguishes him. All this, set in a characteristic, inimitable and unique historical and urban setting: the dark, foggy and smelly slums of Victorian London.

A ritual that, who knows, seems to describe a man who goes beyond the simple – though perverse and sick – sexual enjoyment, typical of many serial killers. A man anything but of humble extraction: an individual capable of hiding himself, of evading, almost mocking investigators, of camouflaging himself among the population, of making fun of the population itself, of acting lucidly, quickly, intelligently and without polluting the crime scene with evidence and traces easily traceable to a well-defined person. A clever individual, skilled with knives. Occultism? Homicide on commission? And here, then, a scenario appears on the horizon: Jack the Ripper considered not as a single person, but as a group of people dedicated to ritual murders. And why do the murders stop so abruptly? Maybe, in the meantime, Jack dies? Or, for some reason unknown to us, voluntarily (or on order) puts an end to the trail of blood? In these details, the case of Jack the Ripper reminds us of the news, equally disturbing and still surrounded by many question marks, related to the so-called “Monster of Florence”.

Cyclical questions, unresolved enigmas. The mocking legacy of Jack the Ripper.